When it comes to capital requirements, you can do it the easy way … or there is the EU way, using Directive 2006/49/EC (Annex VII) - click the pic to enlarge: Snippets from two BBC interviews today But only a little bit. Tuesday, October 14, 2008

It ain't going to work

Despite all the gushing in the media, the drooling about "saviour" Brown (or not, depending on what you read), this "rescue" package is not going to work. It is addressing the symptoms of the problem, not the disease itself.

Despite all the gushing in the media, the drooling about "saviour" Brown (or not, depending on what you read), this "rescue" package is not going to work. It is addressing the symptoms of the problem, not the disease itself.

This is very much like old-fashioned doctoring, before the days of antibiotics, when you tried to cool the fevered patient, in the hope that it would break, and the natural healing process would take over. Sometimes it did work, but most often the patient died.

Here, the infective agent is so powerful that hosing down the "patient" with money is only going to buy time – and very little at that.

The signs of impending disaster are there. John M. Berry in Bloomberg tells it as it is.

"The world's banking system is caught in a vicious trap, with a forced sale of assets at one institution wiping out capital at others holding similar assets," he writes. "Think of it as extraordinarily high reverse leverage."

And, after considering the options, he comes down on the side of blaming "mark to market" accounting. It's way past time to suspend it, he adds, "or somehow to make investors and analysts understand that fire-sale transactions aren't supposed to be having such broad implications."

How deep the rot has infiltrated the system is demonstrated with alarming clarity by Berry's further observations:Asset writedowns and credit losses are approaching $600 billion at the world's biggest banks and securities firms, and the $443 billion worth of capital raised to cover them hasn't been enough to reassure investors. I wonder what that balance would be if the world weren't fixated on mark-to-market accounting.

Berry then cites Harvard University economist Kenneth Rogoff, who said on 10 October that the US "bail-out" will take much more than $700 billion. If it does, he says, the next president will have to demand that Congress provide it.

According to Bloomberg figures, Citigroup Inc., Bank of America Corp. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. have all raised more capital than their writedowns and losses. Nevertheless, the stock prices of the first two have been hammered since the crisis began more than a year ago. (JPMorgan Chase has fared better.)

So one has to ask: How much capital will the U.S. government have to inject into these and other banks -- along with other actions -- to thaw the world's credit freeze? Given the mark-to-market climate, it may take more than the $700 billion authorized in the recent rescue package.

But they are hosing money into a bottomless pit. The potential losses from asset write-downs far exceed in value anything governments can replace. They are, as we noted earlier, "betting the farm", in the hope that, somehow, their actions will defy the laws of economics.

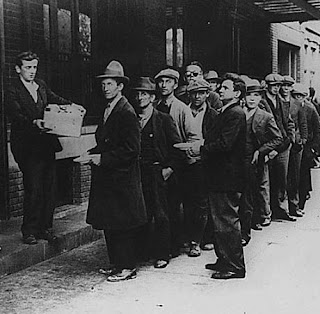

The trouble is, if the bet fails, you – as do we all – end up on the bread line. And that is where we are headed.

COMMENT THREADMad Bank Disease

Talking to a farmer the other day, I was trying to explain the concept of "mark to market", and hit on this wheeze. Imagine, I said, it is 19 March 1996 and you have just bought 150 head of store cattle at £200 each that you are going to fatten up and sell in a few months. How much are those cattle worth?

Talking to a farmer the other day, I was trying to explain the concept of "mark to market", and hit on this wheeze. Imagine, I said, it is 19 March 1996 and you have just bought 150 head of store cattle at £200 each that you are going to fatten up and sell in a few months. How much are those cattle worth?

Simple arithmetic tells you that you have an investment worth £30,000.

But this is 19 March 1996, which means the next day is 20 March 1996. On that day, health minister Stephen Dorrell stood up in parliament and announced a tentative link between the killer disease CJD and Mad Cow Disease (BSE). The meat market didn't go into free fall – it evaporated. I don't think a single beast was sold that day.

So how much are your cattle worth, I ask my farmer. £30,000, he says - he had no intention of selling them. But if you had sold them on the market that day, how much? Er… there was no market. In that case, I declared – feeling very pleased with myself - their value was zero. That's "mark to market". You have to value on a "fire sale" basis, according to what your cattle – your assets – will fetch on the day.

Now, imagine you are a bank. This is your "toxic debt" – your 150 head, nominally worth £30,000. On the basis of that holding, you have been allowed – for the purpose of this example – to borrow a maximum of ten times that amount, which you are allowed to lend, i.e., £300,000. This is called "leverage".

You borrow your £300,000 daily on the short-term wholesale money market at a low interest rate. You then lend it to long-term borrowers at a higher interest rate and make your money out of the difference. That, as Tim Congdon says, is what banks do. Each day, of course, you must pay back your own borrowing, but that is not a problem. You borrow some more, again to match your own lending.

But it is 20 March 1996. Your assets are suddenly worth zero, on a "mark to market" valuation. That, for those technically inclined and who remember the BSE scare, this is the "prion" that has invaded the system, via the "infected feed" of mortgage securitisation and other "complex financial instruments".

You are now too highly leveraged. You are, in fact, insolvent. No commercial bank will lend you any money. You either have to claw back your loans, or you have to top-up your capital – issue more shares. Failing that, you could go to the Bank of England as a lender of last resort. Or you could go to the government for a "bail-out", in which case they'll "nationalise" your farm and put their own manager in. Whatever else happens, you certainly cannot lend any more money.

That – absurdly simplified – is roughly what is happening in to our banks. The banking system is suffering from its own form of BSE - "Mad Bank Disease". The infective agent is "mark to market".

(Republished post)

COMMENT THREADThe European Union way …

"The competent authorities may allow institutions in general or on an individual basis to use a system for calculating the capital requirement for the general risk on traded debt instruments which reflects duration, instead of the system set out in points 17 to 25, provided that the institution does so on a consistent basis."

Easy when you know how!

COMMENT THREADMonday, October 13, 2008

A failure of regulation?

BBC Radio 4 Today Programme

An interview with Sir George Cox, former senior independent director of Bradford and Bingley and Patrick Minford, of Cardiff Business School.

INT: .. [do] you welcome what Gordon Brown has done as perhaps the best plan in the … the best going plan in the world?

Patrick Minford: Yes, I think it's well thought out. And, of course, it's a circumstance we don't want to be in. But given that the banks have failed in this spectacular way and the regulators who were regulating them allowed them to do all this, we really have Hobson's choice.

Later …

INT: Where's the banking sector going over the next few years? …

Patrick Minford: We'll we've got to restore competition and restore credit availability. The great thing we had in the last twenty years was competition between banks and that was very good for the consumer. The trouble is that the regulation of it was very poor and the banks were allowed to take risks they shouldn't have been allowed to do under the Basel conditions. So, as we look forward, we've got to make sure that they play by the rules and also compete with each other and get back to the sort of competitive situation that was so good before this debacle.

INT: George Cox is grimacing as you say all that…

Sir George Cox: Well, I agree we want regulation but the impression's given that there wasn’t regulation before and the FSA just sat here and did what they like. It wasn't. We were supervising the wrong thing. They were concentrating on credit risk which wasn't the problem and not looking at funding risk.

Patrick Minford: That's not true … I think the point is that the banks were not regulated in terms of settng up these special investment vehicles which had enormous risks but they weren't made to put up capital that was proportionate.

Then ... BBC Radio 4 World at One

Prof. Tim Congdon

INT: ... I asked him if thought the government was doing the right thing (partial nationalisation of the banks).

Tim Congdon: No, it's doing quite the wrong thing. It's totally ignoring shareholders' interests. The way this should have been done was by a lender of last resort facility from the Bank of England. Alternatively, the money could have come from the States. And it could have been done through these preferred bonds on a high rate of interest but not at a rate of interest that destroys the businesses. The way the government's going about it is they're effectively stealing from the shareholders. British banks won’t like this and I'm afraid the long run result will be to destroy the competitiveness of Britain's most important industries and one where it's been a world leader in the last twenty or thirty years.

INT: Stealing from shareholders is a very strong way of putting it. If the banks are recapitalised, put on a firmer footing, in the end won't shareholders benefit?

Tim Congdon: No, because they have to share the equity with the government. The Royal Bank of Scotland has £60 billion of shareholders' money at the moment. Because of the way the government's behaved, that is valued by the stock market at a much lower price. If the government comes in at that lower price, then the existing shareholders lose a big chunk of the bank that they own and as a result they're worse off. That’s the big problem with this. And we're going to find in the next few days that the banks will be making a noise and they will warn the government.

INT: But if the bank in which you've invested has behaved recklessly and ended up in this position in the first place, isn't that a danger that you have to take?

Tim Congdon: (agitated) British banks have not behaved recklessly. This is an outrageous slur on the bank industry. British banks have got to comply with regulations. They are inspected all the time by the Financial Services Authority. They're audited and watched and they are not reckless. Can I just say that, an example of this, the allegation that Northern Rock was reckless. Northern Rock has repaid more than half of the loan from the Bank of England already. There was nothing wrong with Northern Rock. There's nothing wrong with the Royal Bank of Scotland. The problem is the government and the Bank of England.

INT: Isn't the problem that the banks got into debt. They took on so-called toxic assets. And in other words actually were in a very dangerous position which was why they're having to be bailed out now.

Tim Congdon: (very agitated) Look, banks are always in debt. That's what their business is. They borrow money in order to lend money.

INT: But it's a question of the ratio isn't it. And what people are saying about the banking industry now is that it's too highly leveraged. It went too far.

Tim Congdon: They're subject to controls and they have met those controls. They have done what they were supposed to do. They're watched all the time by the regulators and the Bank of England, and indeed the Treasury and the government. The way in which this government is behaving will ruin one of our leading industries. The City of London will move elsewhere.

In neither instance did the interviewers follow up, and nor were the issues raised discussed with other commentators or on other bulletins.

COMMENT THREADI've calmed down – a bit

I am now going to explain why this financial crisis, with the incalculable damage it has caused, is entirely the fault of our ruling classes - of which Dr Tannock is a fully paid-up member. I will then explain why and how we must never, ever, let these dangerous fools do the same thing again.

This is going to be a precision demolition job and I'm going to take it in stages. Firstly, to understand this crisis, you really need to know the background.

I've lived with it for thirty years, as I've seen the makings of this regulatory disaster unfold. This is just the final chapter of what is a wholly inevitable, if completely avoidable, disaster.

The best way I know of explaining it is in a semi-autobiographical way, which I hope will give you a deeper insight than just an arid dissertation. I will build the case, piece by piece, brick by brick, each of which I will post on EU Referendum 2. Then I will put it all together here, in one piece, cross-linked so all the evidence and reasoning is there.

The first part - the first brick - starts here:

Part I - A disaster waiting to happen

COMMENT THREAD

Tuesday, 14 October 2008

Posted by

Britannia Radio

at

14:31

![]()