The Tragedy of the S.S. St. Louis

After Kristallnacht in November 1938, many Jews within Germany decided that it was time to leave. Though many German Jews had emigrated in the preceding years, the Jews who remained had a more difficult time because emigration policies had toughened. By 1939, not only were visas needed to be able to enter another country but money was also needed to leave Germany. Since many countries, especially the United States, had immigration quotas, visas were near impossible to acquire within the short time spans in which they were needed. For many, the visas were acquired after it was too late. The opportunity that the S.S. St. Louis presented seemed like a last hope to escape.

Boarding

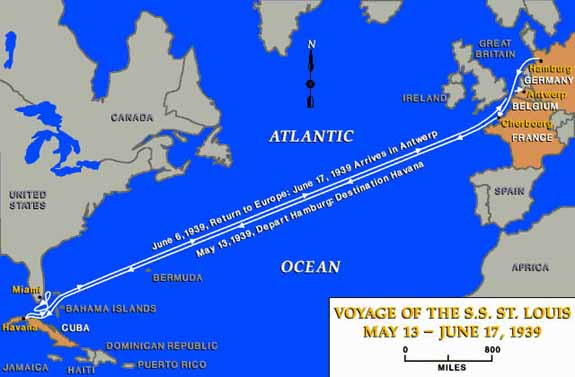

The S.S. St. Louis, part of the Hamburg-America Line (Hapag), was tied up at Shed 76 awaiting its next voyage which was to take Jewish refugees from Germany to Cuba. Once the refugees arrived in Cuba they would await their quota number to be able to enter the United States. The black and white ship with eight decks held room for four hundred first-class passengers (800 Reichsmarks each) and five hundred tourist-class passengers (600 Reichsmarks each). The passengers were also required to pay an additional 230 Reichsmarks for the "customary contingency fee" which was supposed to cover the cost if there was an unplanned return voyage.1 As most Jews had been forced out of their jobs and had been charged high rents under the Nazi regime, most Jews did not have this kind of money. Some of these passengers had money sent to them from relatives outside of Germany and Europe while other families had to pool resources to send even one member to freedom. On Saturday, May 13, 1939, the passengers boarded. Women and men. Young and old. Each person who boarded had their own story of persecution.

One passenger, Aaron Pozner, had just been released from Dachau. On the night of Kristallnacht, Pozner along with 26,000 other Jews had been arrested and deported to concentration camps. While interned at Dachau, Pozner witnessed brutal murders by hanging, drowning, and crucifixion as well as torture by flogging and castrations by a bayonet.2 Surprisingly, one day Pozner was released from Dachau on the condition that he leave Germany within fourteen days. Though his family had very little money, they were able to pool enough money to buy a ticket for him to board the S.S. St. Louis. Pozner said goodbye to his wife and two children, knowing that they would never be able to raise enough money to buy another ticket to freedom. Beaten and forced to sleep amongst bloody animal hides on his journey to reach the ship, Pozner boarded with the knowledge that it was up to him to earn the money to bring his family to freedom.

|

Many other passengers had either left family members behind while some were also going to be meeting relatives that had traveled earlier. As the passengers boarded they remembered the many years of persecution that they had been living under. Some had come out of hiding to board the ship and none were certain that they would not receive the same kind of treatment once aboard. The Nazi flag flying above the ship and the picture of Hitler hanging in the social hall did not allay their fears. Earlier, Captain Gustav Schroeder had given the 231 member crew stern warnings that these passengers were to be treated just like any others. Many were willing to do this, two stewards even carried Moritz and Recha Weiler's luggage for them since they were elderly. But there was one crew member who was disgusted by this policy and was ready to make trouble, Otto Schiendick the Ortsgruppenleiter. Not only was Schiendick ready to make trouble and was constantly trying, he was a courier for the Abwehr (German Secret Police). On this trip, Schiendick was to pick up secret documents about the U.S. military from Robert Hoffman in Cuba. This mission was code-named Operation Sunshine.

The captain made a note in his diary:

There is a somewhat nervous disposition among the passengers. Despite this, everyone seems convinced they will never see Germany again. Touching departure scenes have taken place. Many seem light of heart, having left their homes. Others take it heavily. But beautiful weather, pure sea air, good food, and attentive service will soon provide the usual worry-free atmosphere of long sea voyages. Painful impressions on land disappear quickly at sea and soon seem merely like dreams.3

At 8:00 p.m. on that Saturday (May 13) evening, the ship sailed.

The Trip to Cuba

Only a half an hour after the S.S. St. Louis set sail, it received a message from Claus-Gottfried Holthusen, the marine superintendent of Hapag. The message stated that the S.S. St. Louis was to "make all speed" because there were two other ships (the Flandre and the Orduna) carrying Jewish refugees and heading for Cuba.4 Though there was no explanation for the need to hurry, this message seemed to warn of impending trouble.

The passengers slowly started adjusting to life aboard a large ship. With lots of good food, movies, and swimming pools the mood began to relax a little. Children enjoyed each others' company and made new friendships as well as played childish pranks including locking bathroom stall doors and then climbing out underneath as well as soaping doorknobs. Several times Schiendick attempted to disturb this calm by posting copies of Der Stürmer, by substituting a newsreel with Nazi propaganda for the intended film, and by singing Nazi songs.

For Recha Weiler, who was helped by a steward with her luggage, her main concern was for her husband since his health continued to deteriorate. For over a week, the ship's doctor continued to prescribe medicine for Moritz Weiler but nothing helped. On Tuesday, May 23, Moritz passed away. Captain Schroeder, the purser, and the ship's doctor helped Recha to lay out her husband, provided candles, and found a rabbi on board. Though Recha wanted her husband buried once they reached Cuba, there was no storage facility where the body could be kept. Recha agreed to a burial at sea for her husband. To not unduly disturb the other passengers, it was agreed to hold the funeral at eleven o'clock the same night.

After the funeral rites were observed, the body was wrapped in a large Hapag flag that was then sewn up. Schiendick, trying to make trouble, insisted that the Party regulations stated that the bier, in a burial at sea, should be draped in a swastika flag. Schiendick's proposal was refused. That evening, after a short funeral service the body slid into the sea.

Within half an hour, a depressed crew member jumped overboard at the same location that the body had left the ship. The S.S. St. Louis turned around and sent out search parties. The likelihood of finding the man overboard was small and the delay cost the ship valuable time in its race to Cuba against the Flandre and the Orduna. After several hours of searching, the search was called off and the ship resumed its course.

The news of the two deaths disturbed the passengers and suspicions and tensions increased. For Max Loewe, who was already on edge, the deaths increased his psychosis. Max's wife and two children were increasingly worried about Max but tried to hide it.

Once the Captain received a cable on May 23 which stated that the S.S. St. Louis passengers might not be able to land in Cuba because of Decree 937, he felt it wise to establish a small passenger committee. The committee was to explore possibilities if there were problems landing in Cuba.

Decree 937

In Cuba in early 1939, Decree 55 had passed which drew a distinction between refugees and tourists. The Decree stated that each refugee needed a visa and was required to pay a $500 bond to guarantee that they would not become wards of Cuba. But the Decree also said that tourists were still welcome and did not need visas. The director of immigration in Cuba, Manuel Benitez, realized that Decree 55 did not define a tourist nor a refugee. He decided that he would take advantage of this loophole and make money my selling landing permits which would allow refugees to land in Cuba by calling them tourists. He sold these permits to anyone who would pay $150. Though only allowing someone to land as a tourist, these permits looked authentic, even were individually signed by Benitez, and generally were made to look like visas. Some people bought a large group of these for $150 each and then resold them to desperate refugees for much more. Benitez himself had made a small fortune in selling these permits as well as receiving money from the cruise line. Hapag had realized the advantage of being able to offer a package deal to their passengers, a permit and passage on their ship.

The President of Cuba, Frederico Laredo Bru, and his cabinet did not like Benitez making a great deal of money - that he was unwilling to share - on the loophole in Decree 55. Also, Cuba's economy had begun to stagnate and many blamed the incoming refugees for taking jobs that otherwise would have been held by Cubans.

On May 5, Decree 937 was passed which closed the loophole. Without knowing it, almost every passenger on the S.S. St. Louis had purchased a landing permit for an inflated rate but by the time of sailing, had already been nullified by Decree 937.

Anticipation grew as the S.S. St. Louis neared the Havana harbor. No new mysterious or foreboding telegrams. No more deaths. Passengers enjoyed their last remaining days on ship and wondered what their new lives would be like in Cuba.

Late Friday afternoon, the last full day before the ship was to arrive, Captain Schroeder received a telegram from Luis Clasing (the local Hapag official in Havana) which stated that the St. Louis would have to anchor at the roadstead. Originally planning to dock at Hapag's pier, anchoring at the roadstead had been a concession by President Bru since he still disallowed the St. Louis passengers to land. Captain Schroeder went to sleep that night wondering about this change.

Arrival at Cuba

At three o'clock in the morning, the pilot boarded. Captain Schroeder was anxious to ask the pilot about the reasons that they were to anchor in the harbor but the pilot used the language barrier as a reason not to answer the captain's questions. A bell was rung at four in the morning to awaken the passengers and breakfast was served at half past four.

Cuban police and immigration officials boarded the St. Louis Saturday morning. Then the immigration officials suddenly left with no explanation. The police stayed on board and guarded the accommodation ladder. Several officials boarded but then left without an explanation as to why they had to anchor in the harbor nor gave an assurance that the passengers would be allowed to disembark. As the morning elapsed, family and friends of the passengers who were in Cuba began renting boats and encircling the St. Louis. The passengers on board waved and shouted to those below, but the smaller ships weren't allowed to get too close.

The passengers remained anxious to disembark, not realizing the international and political negotiations which surrounded their fate.

Negotiations and Influences

Manuel BenitezThough a major player in the fate of the refugees since it was he who had signed their landing permits, he continually underestimated President Bru's stance. Benitez constantly maintained that Bru would back down since the St. Louis was allowed in the harbor. He wanted $250,000 in bribes so that he could try to amend his relations with Bru and rescind Decree 937. President Bru refused to listen to Benitez' requests. Though he no longer had access to Bru, he continued to espouse his assurance that Bru would back down. His confident attitude and slick talk convinced a number of influential people that the circumstances were not as serious as they seemed, thus action was not taken.

|

Luis Clasing and Robert Hoffman (local Hapag officials in Havana)

Clasing met several times with Benitez, hoping that Benitez could assure that the passengers would be allowed to disembark. Benitez wanted $250,000 - enough to pay President Bru what would seem a share in the landing permit profits. This was too much for Hapag to pay. Hapag had already given Benitez many "bonuses;" Benitez' request was in response to his lack of influence to change Bru's opinion.

Hoffman needed the ship to land so that he could meet with Schiendick and give him the secret documents. Captain Schroeder had refused to give shore leave to the crew so Hoffman needed to find a way on to the ship or a way to get Schiendick off.

Martin Goldsmith (director of the Relief Committee in Cuba which was financed by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee)

Before the St. Louis arrived in Havana, Goldsmith had repeatedly asked the Joint for additional funds to help the refugees already in Cuba and those about to arrive. The Joint refused. The local Jewish community donated to the Relief Committee but felt that the world should be helping. After the St. Louis arrived, the Joint began to realize the seriousness of the predicament. They would send two professionals to negotiate - but they would not arrive until four days later.

Joseph Goebbels and Anti-Semitism

Goebbels had decided to use the S.S. St. Louis and her passengers in a master propaganda plan. Having sent agents to Havana to stir up anti-Semitism, Nazi propaganda fabricated and hyped the passengers' criminal nature - making them seem even more undesirable. The agents within Cuba stirred anti-Semitism and organized protests. Soon, an additional 1,000 Jewish refugees entering Cuba was seen as a threat.

Stuck in Cuba

The anxiousness and expectation of imminent departure transformed into anxiety and suspiciousness as the waiting was prolonged from hours to days.

On Monday, two days after arriving in Cuba, Hoffman found a way to board the St. Louis. Clasing had allowed Hoffman to go aboard in his place since Clasing was currently occupied about what he was to do with the 250 passengers who were supposed to board the St. Louis on a return voyage to Germany. Would President Bru allow 250 refugees to land so that these passengers waiting in Havana could make their return journey?

Hoffman had already hidden the secret documents in the spine of magazines, inside pens, and inside a walking cane, so he brought these with him to the ship. At the accommodation ladder, Hoffman was told he was allowed onto the ship but that he couldn't bring anything on board. Leaving his magazines and cane behind, Hoffman boarded with the pens. Sent directly to Captain Schroeder, Hoffman used the influence of the Abwehr to force Schroeder into allowing the crew to go to shore. Schroeder, shocked that the Abwehr was connected to his ship, acquiesced. After a quick meeting with Schiendick, Hoffman left the ship. With the change in shore leave policy, Schiendick was able to pick up the magazines and cane and reboard the St. Louis. Now, Schiendick became a major push to head back to Germany with no stop in America for fear of being caught with the secret documents.

On Tuesday, Captain Schroeder called the passenger committee for a meeting for only the second time. The committee had become distrustful of the captain. The St. Louis had sat in the harbor for four days before they were called. No good news had come forward and the passenger committee was asked to send telegrams to influential people, family, and friends asking for help.

Each day that the St. Louis sat in the harbor, Max Loewe became increasingly paranoid. His family had worried before, but Max became extremely disturbed believing that there were many SS and Gestapo on board plotting to arrest him and put him in a concentration camp.

On Tuesday, Max Loewe slit his wrists and jumped overboard at the same spot that the body had gone over the side. Splashing around as he clawed at his arms attempting to pull out his veins, Max Loewe drew the attention of many on board. The siren wailed for man-overboard and a courageous crew member, Heinrich Meier, jumped into the water. The siren and uproar drew police crafts to the area. After some struggle, Meier was able to grab Loewe and push him into a police boat. Loewe kept screaming and had to be tackled to keep him from jumping back into the water. He was taken to an awaiting ambulance and then to a hospital. His wife was not allowed to visit him.

The days continued to progress and the passengers all became increasingly suspicious and fearful. If they were forced back to Germany, they would surely be sent to concentration camps. The possible consequences of their return were loudly suggested in German newspapers and magazines.

For anyone thinking about jumping overboard, the chances were slim of their success with the increased number of police crafts, the searchlights that scanned the ship, and the dangling lights used to illuminate the water.

The world followed the fate of the passengers aboard the St. Louis. Their story was covered around the world. The U.S. Ambassador to Cuba met with an influential member of the Cuban government and spoke diplomatically about the precarious position the Cubans were now in. The Ambassador had spoken without direct instructions from the President but he made the concerns of the U.S. known. The Cuban Secretary of State stated that the subject was to be determined by the cabinet.

On Wednesday, the cabinet met. The passengers aboard the St. Louis would not be allowed to land, not even 250 to allow room for return passengers.

Captain Schroeder began to fear mass suicides on board. Mutiny was also a possibility. With the help of the passenger committee, "suicide patrols" were created to patrol at night.

The two Americans from the Joint had arrived in Havana and by Thursday, June 1, had befriended a couple of influential people who convinced President Bru to reopen negotiations. To their shock though, Bru would not negotiate until the St. Louis was out of Cuban waters. The St. Louis was given notice to leave within three hours. Pleading by Schroener that he needed more time to prepare for departure, the deadline was set back until Friday, June 2 at 10 a.m.

No options were left for the St. Louis, if they did not leave peacefully, they were to be forced out by the Cuban navy.

Leaving Cuba

On Friday morning, the S.S. St. Louis roared up its engines and began to take its leave. Farewells were shouted overboard to friends and family in rented boats below.

The St. Louis was going to encircle Cuba, waiting and hoping for the conclusion of negotiations between the Joint representative, Lawrence Berenson, and President Bru.

The Cuban government wanted $500 per refugee (approximately $500,000 in total). The same amount as required for any refugee to obtain a visa to Cuba. Berenson didn't believe he would have to pay that much, with negotiations, he believed, it would only cost the Joint $125,000.

During the following day, Berenson was approached by several men claiming affiliation with the Cuban government, one identified himself as having powers to negotiate bestowed by Bru. These men insisted that $400,000 to $500,000 were needed to ensure the St. Louis passengers' return. Berenson believed that these men just wanted a cut in the profit by negotiating a higher price. He was wrong.

While the negotiations continued, the St. Louis milled around Cuba and then headed north, following the Florida coastline in the hopes that perhaps the United States would accept the refugees. [Accounts often mention that U.S. Coast Guard ships were following the St. Louis to prevent it from landing, but those ships had actually been sent at the request of Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., because the location of the ship was unknown and he wanted to keep track of it in case a change in policy would allow it to land.]

At this time, it was noticed that because of the lack of time to prepare for leaving port, the St. Louis would run into food and water shortages in less than two weeks. Telegrams continued to arrive insisting the possibility of landing in Cuba or even the Dominican Republic. Once a cable arrived stating the S.S. St. Louis passengers could land on the Isla de la Juventud (formerly Isle of Pines), off of Cuba, Schroeder turned the ship around and headed toward Cuba.

The good news was announced to those on board and everyone rejoiced. Ready and awaiting a new life, the passengers prepared themselves for their arrival the next morning.

The next morning, a telegram arrived stating that landing at the Isla de la Juventud was not confirmed. Shocked, the passenger committee tried to think of other alternatives.

Around noon on Tuesday, June 6, President Bru closed the negotiations. Through a misunderstanding, the money allotment had not been agreed upon and Berenson missed a 48 hour deadline that he didn't know existed. One day later, the Joint offered to pay Bru's every demand but Bru said it was too late. The option of landing in Cuba was officially closed.

With a diminishing supply of food and pressures from Hapag to return to Germany, Captain Schroeder ordered the ship to change heading to return to Europe.

The Return Voyage

The following day, Wednesday, June 7, Captain Schroeder informed the passenger committee that they were returning to Europe. Though the situation was desperate there was still hope that negotiations for their landing in Europe somewhere other than Germany could be possible.

While massive negotiations were beginning, Aaron Pozner rallied some youths aboard to participate in a mutiny. Though they succeeded in capturing the bridge, they did not capture the other strategic locations of the ship. The mutiny was overcome. A crew members suicide by hanging also marked dread on the return voyage.

Through miraculous negotiations, the Joint committee was able to find several countries that would take portions of the refugees. 181 could go to Holland, 224 to France, 228 to Great Britain, and 214 to Belgium.

The passengers disembarked from the S.S. St. Louis from June 16 to June 20. Other ships were transformed to carry the passengers to their locations.

Having crossed the Atlantic Ocean twice, the passengers' original hopes of freedom in Cuba and the U.S. turned into a forlorn effort to escape sure death upon their return to Germany. Feeling alone and rejected by the world, the passengers returned to Europe in June 1939. With World War IIjust months away, many of these passengers were sent East with the occupation of the countries to which they had been sent.

Notes

1Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan Witts, Voyage of the Damned (New York: Stein and Day, 1974), p. 37.

2Thomas, Voyage, p. 31.

3Gustav Schroeder as quoted in Thomas, Voyage, p. 64.

4Thomas, Voyage, p. 65.

Source: This feature is reprinted with permission from Jennifer Rosenberg, a Guide at The Mining Company. Click here to follow this series online at Jen's site about the Holocaust. Copyright © 1998 Jennifer Rosenberg.