William K. Black's Proposal for “Systemically Dangerous Institutions”

William K. Black, Associate Professor of Economics and Law at the University of Missouri – Kansas City, and the former head S&L regulator, has written the following fantastic new proposal concerning the giant, insolvent banks. Posted/reprinted with Professor Black's permission.

Associate Professor of Economics and Law

University of Missouri – Kansas City

blackw@umkc.edu

September 10, 2009

Historically, “too big to fail” was a misnomer – large, insolvent banks and S&Ls were placed in receivership and their “risk capital” (shareholders and subordinated debtholders) received nothing. That treatment is fair, minimizes the costs to the taxpayers, and minimizes “moral hazard.” “Too big to fail” meant only that they were not placed in liquidating receiverships (akin to a Chapter 7 “liquidating” bankruptcy). In this crisis, however, regulators have twisted the term into immunity. Massive insolvent banks are not placed in receivership, their senior managers are left in place, and the taxpayers secretly subsidize their risk capital. This policy is indefensible. It is also unlawful. It violates the Prompt Corrective Action law. If it is continued it will cause future crises and recurrent scandals.

On October 16, 2006, Chairman Bernanke delivered a speech explaining why regulators must not allow banks with inadequate capital to remain open.

http://federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20061016a.htm

Capital regulation is the cornerstone of bank regulators' efforts to maintain a safe and sound banking system, a critical element of overall financial stability. For example, supervisory policies regarding prompt corrective action are linked to a bank's leverage and risk-based capital ratios. Moreover, a strong capital base significantly reduces the moral hazard risks associated with the extension of the federal safety net.The Treasury has fundamentally mischaracterized the nature of institutions it deems “too big to fail.” These institutions are not massive because greater size brings efficiency. They are massive because size brings market and political power. Their size makes them inefficient and dangerous.

Under the current regulatory system banks that are too big to fail pose a clear and present danger to the economy. They are not national assets. A bank that is too big to fail is too big to operate safely and too big to regulate. It poses a systemic risk. These banks are not “systemically important”, they are “systemically dangerous.” They are ticking time bombs – except that many of them have already exploded.

We need to comply with the Prompt Corrective Action law. Any institution that the administration deems “too big to fail” should be placed on a public list of “systemically dangerous institutions” (SDIs). SDIs should be subject to regulatory and tax incentives to shrink to a size where they are no longer too big to fail, manage, and regulate. No single financial entity should be permitted to become, or remain, so large that it poses a systemic risk.

SDIs should:

1. Not be permitted to acquire other firms

2. Not be permitted to grow

3. Be subject to a premium federal corporate income tax rate that increases with asset size

4. Be subject to comprehensive federal and state regulation, including:

a. Annual, full-scope examinations by their primary federal regulator

b. Annual examination by the systemic risk regulator

c. Annual tax audits by the IRS

d. An annual forensic (anti-fraud) audit by a firm chosen by their primary federal regulator

e. An annual audit by a firm chosen by their primary federal regulator

f. SEC review of every securities filing

5. A prohibition on any stock buy-backs

6. Limits on dividends

7. A requirement to follow “best practices” on executive compensation as specified by their primary federal regulator

8. A prohibition against growth and a requirement for phased shrinkage

9. A ban (which becomes effective in 18 months) on having an equity interest in any affiliate that is headquartered in or doing business in any tax haven (designated by the IRS) or engaging in any transaction with an entity located in any tax haven

10. A ban on lobbying any governmental entity

11. Consolidation of all affiliates, including SIVs, so that the SDI could not evade leverage or capital requirements

12. Leverage limits

13. Increased capital requirements

14. A ban on the purchase, sale, or guarantee of any new OTC financial derivative

15. A ban on all new speculative investments

16. A ban on so-called “dynamic hedging”

17. A requirement to file criminal referrals meeting the standards set by the FBI

18. A requirement to establish “hot lines” encouraging whistleblowing

19. The appointment of public interest directors on the BPSR’s board of directors

20. The appointment by the primary federal regulator of an ombudsman as a senior officer of the SDI with the mission to function like an Inspector General

Bank President Admitted that All Credit Is Created Out of Thin Air With the Flick of a Pen Upon the Bank's Books

In First National Bank v. Daly (often referred to as the "Credit River" case) the court found: that the bank created money "out of thin air":

[The president of the First National Bank of Montgomery] admitted that all of the money or credit which was used as a consideration [for the mortgage loan given to the defendant] was created upon their books, that this was standard banking practice exercised by their bank in combination with the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneaopolis, another private bank, further that he knew of no United States statute or law that gave the Plaintiff [bank] the authority to do this.The court also held:

The money and credit first came into existence when they [the bank] created it.(Here's the case file).

Justice courts are just local courts, and not as powerful or prestigious as state supreme courts, for example. And it was not a judge, but a justice of the peace who made the decision.

But what is important is that the president of the First National Bank of Montgomery apparently admitted that his bank created money by simply making an entry in its book, which means - as we have previously pointed out - that the story we've all been told that bank deposits and reserves precede loans is false.

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 2009

Arguments for Deflation: Unemployment, Debt and Deleveraging, the Pension Crisis, Collapse of the Shadow Banking System, and Interest on Reserves

As Absolute Return Partners wrote in its July newsletter:

The most important investment decision you will have to make this year and possibly for years to come is whether to structure your portfolio for deflation or inflation.

So which is it, inflation or deflation?

This is obviously a hot topic of debate, and experts weigh in on both sides. I’ve analyzed this issue in numerous posts, but every day there are new arguments one way or the other from some very smart people.

Because the arguments for inflation are so obvious and widely-discussed (bailouts, quantitative easing, Fed purchasing treasuries, etc.), I will not discuss them here (other than pointing to an interesting new argument for inflation by Andy Xie).

How Bad Could It Get?

The biggest deflation bears are rather pessimistic:

- David Rosenberg says that deflationary periods can last years before inflation kicks in

- Renowned economist Dr. Lacy Hunt says that we may have 15-20 years of deflation

- PhD economist Steve Keen says that – unless we reduce our debt – we could have a “never-ending depression”

These are the most pessimistic views I have run across. Most deflationists think that a deflationary period would last for a shorter period of time.

The Best Recent Arguments for Deflation

Following are some of the best arguments for deflation.

Unemployment

Wall Street Journal’s Scott Patterson writes that we won’t get inflation until unemployment is down below 5%:

A rule of thumb is that inflation doesn’t become sticky until the unemployment rate dips below 5%…

“I see very little prospect of accelerating inflation” partly because of the employment outlook, said Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Economy.com. “I don’t think the risk shifts toward inflation until 2011, or even 2012.”

It could take a lot longer for unemployment to go back down to 5% (and for consumers to have more money to spend again).

(Note: hyperinflation is obviously an entirely different animal. For example, there was rampant unemployment in the Weimar Republic during its bout with hyperinflation ).

Debt Overhang and Deleveraging

Steve Keen argues that the government’s attempts to increase lending won’t work, consumers will keep on deleveraging from their debt, and that – unless debt is slashed – the massive debt overhang will keep us in a deflationary environment for a long time.

Mish writes:

An over-leveraged economy is one prone to deflation and stagnant growth. This is evident in the path the Japanese took after their stock and real estate bubbles began to implode in 1989.

Leverage is increasing again, according to an article in Bloomberg:

Banks are increasing lending to buyers of high-yield company loans and mortgage bonds at what may be the fastest pace since the credit-market debacle began in 2007…

“I am surprised by how quickly the market has become receptive to leverage again,” said Bob Franz, the co-head of syndicated loans in New York at Credit Suisse…

Indeed, as I have repeatedly pointed out, Bernanke, Geithner, Summers and the chorus of mainstream economists have all acted as enablers for increasing leverage.

Mish continues:

Creative destruction in conjunction with global wage arbitrage, changing demographics, downsizing boomers fearing retirement, changing social attitudes towards debt in every economic age group, and massive debt leverage is an extremely powerful set of forces.

Bear in mind, that set of forces will not play out over days, weeks, or months. A Schumpeterian Depression will take years, perhaps even decades to play out.

Thus, deflation is an ongoing process, not a point in time event that can be staved off by massive interventions and Orwellian Proclamations “We Saved The World”.

Bernanke and the Fed do not understand these concepts, nor does anyone else chanting that pending hyperinflation or massive inflation is coming right around the corner, nor do those who think new stock market is off to new highs. In other words, almost everyone is oblivious to the true state of affairs.

Pension Crisis

Pension expert Leo Kolivakis writes:

The global pension crisis is highly deflationary and yet very few commentators are discussing this.

Collapse of the Shadow Banking System

Hoisington’s Second Quarter 2009 Outlook states:

One of the more common beliefs about the operation of the U.S. economy is that a massive increase in the Fed’s balance sheet will automatically lead to a quick and substantial rise in inflation. [However] An inflationary surge of this type must work either through the banking system or through non-bank institutions that act like banks which are often called “shadow banks”. The process toward inflation in both cases is a necessary increasing cycle of borrowing and lending. As of today, that private market mechanism has been acting as a brake on the normal functioning of the monetary engine.

For example, total commercial bank loans have declined over the past 1, 3, 6, and 9 month intervals. Also, recent readings on bank credit plus commercial paper have registered record rates of decline. The FDIC has closed a record 52 banks thus far this year, and numerous other banks are on life support. The “shadow banks” are in even worse shape. Over 300 mortgage entities have failed, and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are in federal receivership. Foreclosures and delinquencies on mortgages are continuing to rise, indicating that the banks and their non-bank competitors face additional pressures to re-trench, not expand. Thus far in this unusual business cycle, excessive debt and falling asset prices have conspired to render the best efforts of the Fed impotent.

Ellen Brown argues that the break down in the securitized loan markets (especially CDOs) within the shadow banking system dwarfed other types of lending, and argues that the collapse of the securitized loan market means that deflation will – with certainty – continue to trump inflation unless conditions radically change.

Support for Brown’s argument comes from several sources.

As the Washington Times notes:

“Congress’ demand that banks fill in for collapsed securities markets poses a dilemma for the banks, not only because most do not have the capacity to ramp up to such large-scale lending quickly. The securitized loan markets provided an essential part of the machinery that enabled banks to lend in the first place. By selling most of their portfolios of mortgages, business and consumer loans to investors, banks in the past freed up money to make new loans. . . .“The market for pooled subprime loans, known as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), collapsed at the end of 2007 and, by most accounts, will never come back. Because of the surging defaults on subprime and other exotic mortgages, investors have shied away from buying the loans, forcing banks and Wall Street firms to hold them on their books and take the losses.”

Senior economic adviser for UBS Investment Bank, George Magnus, confirms:

The restoration of normal credit creation should not be expected, until the economy has adjusted to the disappearance of shadow bank credit, and until banks have created the capacity to resume lending to creditworthy borrowers. This is still about capital adequacy, where better signs of organic capital creation are welcome. More importantly now though, it is about poor asset quality, especially as defaults and loan losses rise into 2010 from already elevated levels.

And McClatchy writes:

The foundation of U.S. credit expansion for the past 20 years is in ruin. Since the 1980s, banks haven’t kept loans on their balance sheets; instead, they sold them into a secondary market, where they were pooled for sale to investors as securities. The process, called securitization, fueled a rapid expansion of credit to consumers and businesses. By passing their loans on to investors, banks were freed to lend more.

Today, securitization is all but dead. Investors have little appetite for risky securities. Few buyers want a security based on pools of mortgages, car loans, student loans and the like.

“The basis of revival of the system along the line of what previously existed doesn’t exist. The foundation that was supposed to be there for the revival (of the economy) . . . got washed away,” [economist James K.] Galbraith said.

Unless and until securitization rebounds, it will be hard for banks to resume robust lending because they’re stuck with loans on their books.

Fed Paying Interest on Reserves

And Naufal Sanaullah writes:

So if all of this printed money is being used by the Fed to purchase toxic assets, where is it going?

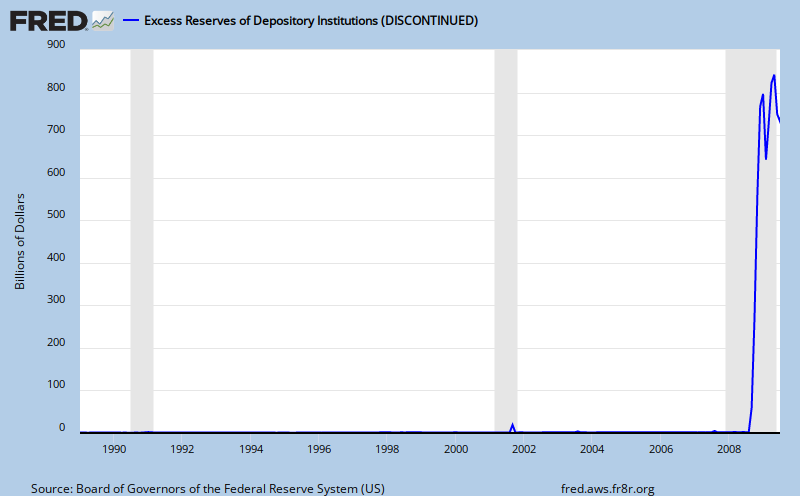

Excess reserves, of course. Counting for $833 billion of the Fed’s liabilities, the reserve balance with the fed has skyrocketed almost 9000% YoY. Excess reserves, balances not used to satisfy reserve requirements, total $733 billion, up over 38,000%!

The Fed pays interest on these reserves, and with an interest rate (return on capital) comes opportunity cost. Banks hoard the capital in their reserves, collecting a risk-free rate of return, instead of lending it out into the economy. But what happens as more loan losses occur and consumer spending grinds to a halt? The Fed will lower (or get rid of) this interest on reserves.

And that is when the excess liquidity synthesized by the Fed, the printed money, comes rushing in and inflates goods prices.

Of course, most people who are arguing we will have deflation for a while believe that we might eventually get inflation at some point in the future.

Bottleneck Theory of Inflation

Andy Xie has an interesting theory about inflation.

Specifically, Xie argues that bottlenecks can form in certain asset classes - such as oil -even in a weak economy, which can lead to inflation:

Conventional wisdom says inflation will not occur in a weak economy: The capacity utilization rate is low in a weak economy and, hence, businesses cannot raise prices. This one-dimensional thinking does not apply when there are structural imbalances. Bottlenecks could first appear in a few areas. Excess liquidity tends to flow toward shortages, and prices in those target areas could surge, raising inflation expectations and triggering general inflation. Another possibility is that expectations alone would be sufficient to bring about general inflation.

Oil is the most likely commodity to lead an inflationary trend. Its price has doubled from a March low, despite declining demand. The driving force behind higher oil prices is liquidity. Financial markets are so developed now that retail investors can respond to inflation fears by buying exchange traded funds individually or in baskets of commodities.

Oil is uniquely suited as an inflation hedging device. Its supply response is very low. More than 80 percent of global oil reserves are held by sovereign governments that don't respond to rising prices by producing more. Indeed, once their budgetary needs are met, high prices may decrease their desire to increase production. Neither does demand fall quickly against rising prices. Oil is essential for routine economic activities, and its reduced consumption has a large multiplier effect. As its price sensitivities are low on demand and supply sides, it is uniquely suited to absorb excess liquidity and reflect inflation expectations ahead of other commodities.

If central banks continue refusing to raise interest rates during these weak economic times, oil prices may double from their current levels. So I think central banks, especially the Fed, will begin raising interest rates early next year or even late this year. I don't think it would raise rates willingly but wants to cool inflation expectations by showing an interest in inflation. Hence, the Fed will raise interest rates slowly, deliberately behind the curve. As a consequence, inflation could rise faster than interest rates

"For the Week Ended Last Friday ... Insiders Sold 6.31 Shares for Every One They Bought"

Mark Hulbert notes:

The message from the insiders is rather sobering: They are selling a whole lot more of their companies' stock than they are buying. The net difference is even larger than it was two months ago, when I noted that insiders were already selling at a greater pace than at any time since the top of the bull market in the fall of 2007...

Consider the latest data from the Vickers Weekly Insider Report, published by Argus Research. For the week ended last Friday, according to Vickers, insiders sold 6.31 shares for every one than they bought. The comparable ratio two months ago was 4.16-to-1, and at the March lows the ratio was 0.34-to-1.

As Vickers editor David Coleman puts it in the latest issue of his newsletter: "Given the dramatic decline in our sell/buy ratios over a relatively short period of time and the robust rally we have seen in the broad market averages, we expect the overall markets to trade flat to downward in the intermediate term -- and with increasing volatility. Overall insider sentiment is bearish by nearly all metrics we track."

TrimTabs and ZeroHedge claim that the insider sell/buy ratio has actually been much higher than 6.31 over the last couple of weeks.

Fed Admits that Tight Lending and Unemployment May Slow Recovery

I have repeatedly said that the banks won't significantly increase their lending to individuals and small businesses until the economy stabilizes, no matter how much money the government gives them.

I have repeatedly said that the whole concept of a "jobless recovery" given the economic fundamentals we have currently is nonsense, and that the rising tide of unemployment will keep the economy on the ropes for some time.

Now, as Bloomberg points out, the Fed may finally be grudgingly admitting as much:

Whether the Fed's policy of requiring more capital is good or bad is beyond the scope of this essay.The Federal Open Market Committee, at the conclusion tomorrow of a two-day meeting, will probably maintain its assessment that “tight” bank credit is impeding growth, said economists including former Fed Governor Lyle Gramley. Lending contracted for five straight weeks through Sept. 9, a drop that in part reflects Fed orders to banks to raise more capital and toughen lending standards, analysts say.

A failure to restore the flow of bank credit carries the risk that the economic recovery will be slower than the Fed anticipates, or even that the U.S. lapses into another recession, economists say...

“The financial system is still far from healthy and tight credit is likely to put a damper on growth for some time to come” [San Francisco Fed President Janet Yellen said in a Sept. 14 speech].

The Fed has taken other steps to make sure banks avoid riskier loans. In July 2008, it tightened mortgage rules by requiring lenders to determine a borrower’s ability to repay and barring other practices that led to the collapse of the housing market.

Minimum regulatory-capital requirements may change as officials in the U.S. and abroad craft new financial rules. Consumers are less credit-worthy as the job market deteriorates and after a record loss of wealth from plunging share prices and real estate values.

Rising unemployment will slow the pace of the recovery, Bernanke said on Sept. 15.

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 2009

Satyajit Das: “Derivatives and Debt Are the Needles of Finance”

I have repeatedly argued that:

- Derivatives are still extremely dangerous

- The insiders are killing any real reform

- Credit default swaps aren't meaningfully being regulated, as only "standard" CDS contracts are subject to regulation

- Even standard contracts might not really end up being regulated

- Most economists have acted like team doctors for the financial giants, pushing increased levels of leverage (i.e. debt - to the extent that increased leverage means borrowing more) like sports docs push injured athletes to get a shot of steroids and get back on the field

Derivatives expert Satyajit Das confirms all of these points (and provides some memorable quotes in the process):

The industry and its key lobby group (ISDA – International Swaps & Derivatives Association) are well practiced in the art of regulatory skullduggery.

Derivatives, it will be argued, are soooo complicated that only derivative traders themselves can properly “regulate” them. If this fails then there will be more subtle rhetorical thrusts.

The new CCP [new centralised counterparty] is only for “standardised” derivatives. Already, there are impassioned semantic debates about what is meant by “standard derivatives” and whether they can actually be cleared through the CCP...

The complexity of modern derivatives has little to do with risk transfer and everything to do with profits. As new products are immediately copied by competitors, traders must “innovate” to maintain revenue by increasing volumes or creating new structures. Complexity delays competition, prevents clients from unbundling products and generally reduces transparency. Frequently, the models used to price, hedge and determine the profitability also manage to confuse managers and controllers within banks themselves allowing traders to book large fictitious “profits” that their bonuses are based on...

Warren Buffet once described bankers in the following terms: “Wall Street never voluntarily abandons a highly profitable field. Years ago… a fellow down on Wall Street…was talking about the evils of drugs…he ranted on for 15 or 20 minutes to a small crowd…then…he said: “Do you have any questions?” One bright investment banking type said to him: “yeah, who makes the needles?

Derivatives and debt are the needles of finance and bankers will continue to supply them ... for the foreseeable future as long as there is money to be made in the trade.

Dear President Obama: Blogs Fact-Check and Put Stories in Context Much Better than the Corporate Media

President Obama said yesterday:

I am concerned that if the direction of the news is all blogosphere, all opinions, with no serious fact-checking, no serious attempts to put stories in context, that what you will end up getting is people shouting at each other across the void but not a lot of mutual understanding.

But as Dan Rather pointed out in July, the quality of journalism in the mainstream media has eroded considerably, and news has been corporatized, politicized, and trivialized.

Rather also pointed out that “roughly 80 percent” of the media is controlled by no more than six, and possibly as few as four, corporations. As I wrote in July:

This is only newsworthy because Rather said it. This fact has been documented for years, as shown by the following must-see charts prepared by:

And check out this list of interlocking directorates of big media companies from Fairness and Accuracy in Media, and this resource from the Columbia Journalism Review to research a particular company.

This image gives a sense of the decline in diversity in media ownership over the last couple of decades:

As I have also documented, there are four major problems with the mainstream reporting:

- Widespread self-censorship by journalists

- Censorship from editors and producers

- Pro-war bias

- Government censorship

(Oh, and also moolah)

Moreover, as I wrote in March:

The whole debate about blogs versus mainstream media is nonsense.

In fact, many of the world's top PhD economics professors and financial advisors have their own blogs...

The same is true in every other field: politics, science, history, international relations, etc.

So what is "news"? What the largest newspapers choose to cover? Or what various leading experts are saying - and oftentimes heatedly debating one against the other?

As blogger Michael Rivero pointed out years ago, mainstream newspapers aren't losing readers because of the Internet as an abstract new medium. They are losing readers because they have become nothing but official stenographers for the powers-that-be, and people have lost all faith in them.

Indeed, only 5% of the pundits discussing various government bailout plans on cable news shows are real economists. Why not hear what real economists and financial experts say?

To the extent that blogs offer actual news and the mainstream media does not, the latter will continue to lose eyeballs and ad revenues to the former.

In reality, the best blogs offer far more fact-checking and context then the mainstream media.

If Credit is Not Created Out of Excess Reserves, What Does That Mean?

We've all been taught that banks first build up deposits, and then extend credit and loan out their excess reserves.

But critics of the current banking system claim that this is not true, and that the order is actually reversed.

Sounds crazy, right?

Certainly.

But as PhD economist Steve Keen pointed out last week, 2 Nobel-prize winning economists have shown that the assumption that reserves are created from excess deposits is not true:

In other words, if the conventional view that excess reserves (stemming either from customer deposits or government infusions of money) lead to increased lending were correct, then Kydland and Prescott would have found that credit is extended by the banks (i.e. loaned out to customers) after the banks received infusions of money from the government. Instead, they found that the extension of credit preceded the receipt of government monies.The model of money creation that Obama’s economic advisers have sold him was shown to be empirically false over three decades ago.

The first economist to establish this was the American Post Keynesian economist Basil Moore, but similar results were found by two of the staunchest neoclassical economists, Nobel Prize winners Kydland and Prescott in a 1990 paper Real Facts and a Monetary Myth.

Looking at the timing of economic variables, they found that credit money was created about 4 periods before government money. However, the “money multiplier” model argues that government money is created first to bolster bank reserves, and then credit money is created afterwards by the process of banks lending out their increased reserves.

Kydland and Prescott observed at the end of their paper that:

Introducing money and credit into growth theory in a way that accounts for the cyclical behavior of monetary as well as real aggregates is an important open problem in economics.

Keen explained in an interview Friday that 25 years of research shows that creation of debt by banks precedes creation of government money, and that debt money is created first andprecedes creation of credit money.

As Mish has previously noted:

Conventional wisdom regarding the money multiplier is wrong. Australian economist Steve Keen notes that in a debt based society, expansion of credit comesfirst and reserves come later.

And as Edward Harrison writes:

Central to [Keen's] ideas is the concept that demand for credit creates loans which create reserves, which is the opposite causality of what one sees in neoclassical economics.

This angle of the banking system has actually been discussed for many years by leading experts:

“[Banks] do not really pay out loans from the money they receive as deposits. If they did this, no additional money would be created. What they do when they make loans is to accept promissory notes in exchange for credits to the borrowers' transaction accounts."

- 1960s Chicago Federal Reserve Bank booklet entitled “Modern Money Mechanics”

“The process by which banks create money is so simple that the mind is repelled.”

- Economist John Kenneth Galbraith[W]hen a bank makes a loan, it simply adds to the borrower's deposit account in the bank by the amount of the loan. The money is not taken from anyone else's deposit; it was not previously paid in to the bank by anyone. It's new money, created by the bank for the use of the borrower.

- Robert B. Anderson, Secretary of the Treasury under Eisenhower, in an interview reported in the August 31, 1959 issue of U.S. News and World Report“Do private banks issue money today? Yes. Although banks no longer have the right to issue bank notes, they can create money in the form of bank deposits when they lend money to businesses, or buy securities. . . . The important thing to remember is that when banks lend money they don’t necessarily take it from anyone else to lend. Thus they ‘create’ it.”

-Congressman Wright Patman, Money Facts (House Committee on Banking and Currency, 1964)"The modern banking system manufactures money out of nothing. The process is perhaps the most astounding piece of sleight of hand that was ever invented.

- Sir Josiah Stamp, president of the Bank of England and the second richest man in Britain in the 1920s.

Banks create money. That is what they are for. . . . The manufacturing process to make money consists of making an entry in a book. That is all. . . . Each and every time a Bank makes a loan . . . new Bank credit is created -- brand new money.

- Graham Towers, Governor of the Bank of Canada from 1935 to 1955

Indeed, some critics of the current banking system - like Ellen Brown - claim that the entire credit-creation system is an accounting sleight-of-hand, and that banks simply enter into loan agreements, and then obtain the reserves later from the Fed or in the open market. In other words, they claim that banks extend money first, and then increase their reserves on their books later to cover the loans.

So What Does It Mean?

So what does it mean that loans and debt are created first, and then reserves and credit come later?

There are several results.

First, it makes it less likely than most people think that the giant banks will increase the amount of money they're loaning out to individuals and small businesses. Specifically, since loans are made before new infusions of government cash (Kydland and Prescott), there is not a simple cause-and-effect relationship. So the bailouts to the banks will notnecessarily encourage them to make more loans. Indeed, the heads of the big banks havethemselves said that they won't really increase such loans until the economy fundamentally stabilizes (no matter how much money the government gives them).

As Mish writes today:

A funny thing happened to the inflation theory: Banks aren't lending and proof can be found in excess reserves at member banks.

Excess Reserves

...

In practice, banks lend money and reserves come later. When defaults pile up, the Fed prints reserves to cover bank losses. Thus, those "excess reserves" aren't going anywhere. They are needed to cover losses. It's best to think of those reserves as a mirage. They don't really exist.

Second, if banks won't increase their lending in response to government funds, then that argues against inflation and for continuing stagnation in the economy.

Is This Method of Credit-Creation Unsustainable?

Going beyond what most economists believe or will publicly discuss (and going beyond what I have any background or inside information to confirm) - monetary reformers like Ellen Brown argue that the entire banking system is based upon a fraud. Specifically, she and other monetary reformers argue that the banks have intentionally spread the false reserves-and-credit first, loans-and-debt later story to confuse people into thinking that the banks are better capitalized than they really are and that the Federal Reserve is keeping better oversight than it really is.

Moreover, many monetary reformers argue that the truth of loans-before-reserves is hidden in order to obscure the alleged fact that the entire financial system is built on nothing but air. Specifically, Brown argues that unless more and more debt is continually created, since money creation follows debt creation, what we think of as the money supply will shrink, and the economy will crash. In other words, they say that we a massive, ever-expanding debt bubble has been blown for many decades, and that the myth that banks make loans out of their excess reserves helps to fuel the bubble.

Some evidence for that argument comes from a September 30, 1941 hearing in the House Committee on Banking and Currency, where the then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve (Mariner S. Eccles) said:

That is what our money system is. If there were no debts in our money system, there wouldn’t be any money.Monetary reformers argue that the government should take the power of money creation back from the private banks and the Federal Reserve system.

Do the monetary reformers go too far? If so, what should the reality of the way credit is created mean for us and the stability of the economy?