David M. Glantz Fights for the Truth About Stalingrad

By Gene Santoro | World War II Conversations | Single Page | 4 comments | Print This Post | Email This Post

'The Soviet troops are sacrificial lambs. Divisions that come in with 10,000 men have 500 the next day'

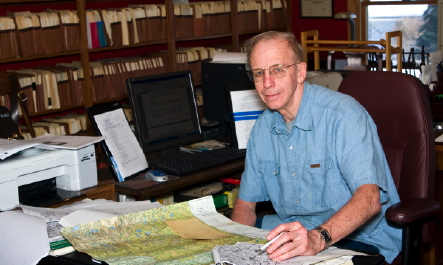

A retired U.S. Army colonel fluent in Russian, David M. Glantz writes data-rich tomes that synthesize his research in the recently opened Soviet archives. His goal: to debunk long-standing myths with what he calls "ground truth." His latest epics, To the Gates of Stalingrad and Armageddon in Stalingrad(both published in 2009, with a third volume due next year), recast history's biggest battle in a new light. For example, he and coauthor Jonathan M. House are the first historians to use archival material from the brutal Soviet secret police force, the NKVD, which was charged with maintaining discipline in the Red Army. "Its documents are surprisingly candid about declining morale, the amount of censorship, numbers of deserters, and so on," Glantz says, "a human dimension of the battle often speculated upon but never before documented."

SUBSCRIBE TODAY

- Did you enjoy our article?

- Read more inWorld War IImagazine

- Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

What do you mean by ground truth?

I mean examining the records of both sides to finally strip away the myths and begin to restore reality. You can't reach judgments regarding political, diplomatic, economic, or social factors in the war as a whole unless you have reached sound decisions regarding how the war was conducted, to what end it was conducted, and so forth. Historians today are focused not on operational but social issues. But it all sits on the structure of military reality.

Why choose Stalingrad?

There have been hundreds of books on the battle, dating back to the early 1950s. Many early ones were German memoirs, or about specific Germans. In the 1980s and 1990s, many were essentially derived from those sources plus a narrow base of Soviet sources, the predominant one being memoirs by Vasily Chuikov, who headed the Soviet Sixty-second Army; those are quite accurate and very good. But over time, all these books incorporated the same basic conclusions about the campaign as a whole and the battle for the city. And many of those conclusions are simply wrong.

For example?

One common perception is this: unlike in Barbarossa in 1941, where the Soviet army resisted the Wehrmacht and took immense casualties, during Blau in 1942 Stalin very quickly withdraws his forces and decides to trade space for time; once he gets back to a more defensible line, he launches a counteroffensive. That's flat wrong. From Blau's very beginning, Stalin's orders are to stand and fight. His strategy throughout the war is to attack everywhere at every time, in the belief that somewhere someone will break.

Does the Red Army attack on the road to Stalingrad?

Despite widespread belief otherwise, there's some horrendous fighting, generally caused by Soviet forces in counterattacks, counterstrokes, and even counteroffensives. The most important comes in July along the Germans' northern flank. Stalin commits a tank army as well as other new formations that didn't exist in 1941. There are major tank battles, 500 to 1,000 Soviet tanks.

What do these achieve?

In the first operations they're very poorly led, and so don't achieve that much—except that they bleed the Germans. The same thing happens at the end of July: two new Soviet tank armies appear at the bend of the Don River and launch counterattacks in support of the new Sixty-second Army. This huge tank battle goes on for nearly three weeks, and throws the German plan right out the window.

Why?

The number of Germans in the attacking infantry force is far smaller than in 1941, and many of the infantry units trailing in the panzers' wake are Romanians and Italians, who aren't really interested in dying for the führer. So in 1942, although Russian armies are encircled and their fighting ability destroyed, the troops get out and either go to ground or rejoin the Red Army later.