The Challenge Of The Spaceship: Spaceflight As It Should Have Been

And As It Was

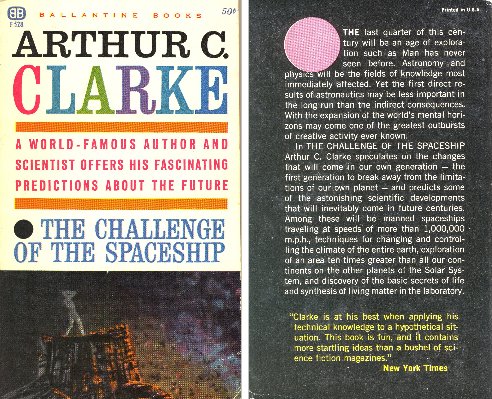

The phrase “The Challenge of the Spaceship” is the title of an early 1950s popular science article by the late Arthur C. Clarke(1917-2008), best known as the scenarist for Stanley Kubrick’s enigmatic space travel film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); Clarke, a radio-electronics engineer who switched to writing science fiction stories in the late 1940s and became a dean of the genre, used the title again when he anthologized that article with a dozen others for book publication in 1955. (There were republications with additional material in subsequent years.) With other science fiction writers – like John W. Campbell,Robert A. Heinlein, and Isaac Asimov – Clarke helped immensely to inspire the actual space program in the West, chiefly of course in the United States. The boredom of the Space Shuttle in service and the pointlessness of its destination the International Space Station have consigned to oblivion the memory of the actual space program, the climax of which came with the moon landings of the three years 1969 to 1972. NASA, fully complicit in the public’s indifference to its bailiwick, still sends robotic probes to the planets and moons, with diverting results, but has long since lost the courage necessary for manned exploration of the solar system.

When the Obama administration recently killed off the Ares Orbital Booster and Orion Upper Stage, NASA could muster no persuasive objection. Nor did the public care. No American or European astronaut will set foot on the moon or Mars in the foreseeable future although the Chinese have announced their interest in establishing a lunar presence. The USA will in fact not possess even so much as its own manned orbital capability starting in 2011.

Planetary exploration, that last great endeavor of what Oswald Spengler called Faustian Culture – the spiritual movement that built the great cathedrals of Christian Europe and that invented science and technology – is dead. On its tomb we see rise the social-welfare “nanny state,” multiculturalism, affirmative action, Gaia-worship, the entertainment industry, and an education establishment nationalized, feminized, and purged of intellectual rigor so as to make room for insipid self-esteem and the cultivation of homey errands that (how to put it?) teenage girls can do. Contemporary society, like the teenage girl, takes interest in itself primarily, in a preening and thoroughly petty way. The postmodern social order dresses women up as soldiers, it puts them in dangerous aircraft as pilots, and it even sends some of them on Shuttle missions, but it lacks the outward urge of the true pioneering spirit. The de-spirited dhimmi-polity meanwhile cozies up to Stone Age barbarians but refuses to rebuild its own fallen towers ten years after they fell.

According to science fiction, the agenda should have realized itself much more aggressively than it did. Instead of ending in a pathetic whimper, it should have thundered outward leap by fiery leap – to the moon, to Mars, to the asteroids, and from the outer planets, using novel propulsion systems, to the worlds of the nearby stars. Men should have reached the moon by 1960 and Mars by 1970. Even the Apollo Program, with its successful missions, disappointed those who had imagined space travel in a literary or speculative mode beginning in the 1930s. The preparations for launching the Saturn V rocket involved the tedium of weeks. The take-off of the Saturn V, as tall as a forty-story building and as heavy as a nuclear submarine, resulted only in a cramped spider-like contraption actually touching down on the lunar surface. The returning capsule parachuted into the ocean, bobbing there until Navy helicopters plucked it to safety on a flattop. A frightened Space Agency cancelled the last three Apollo missions, considering that statistically it had run out of luck. NASA managers concluded that the agency could not survive public horror over astronauts stranded and perishing on the lunar surface. In the longer term, however, it turned out that the agency could no more survive timidity than calamity.

The Space Shuttle, like the Saturn V, also roars off in a lavish display after a weeklong countdown. The Shuttle then remains in humble near-earth orbit, flying inverted as though to spurn the stars. Despite its go-nowhere humbleness, the Shuttle has killed four times as many astronauts as the Apollo hardware did. For what? And how might it have been otherwise?

For one thing, the scientific visionaries and their co-visionaries the science fiction writers rarely – I refrain from saying never– foresaw the conquest of space as the jurisdiction of a government bureaucracy. Rather, going back to Jules Verne, they tended to see it as a form of enterprise on the order of building a transcontinental railroad or laying an undersea cable connecting North America with Europe. Indeed, none of the early rocketry pioneers and spaceflight prophets enjoyed state sponsorship. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935) taught mathematics in provincial high schools in Russia while writing eccentric books about sending rockets into space and colonizing the solar system. Robert H. Goddard (1882-1945), an American, began experimenting in liquid-fueled rocket propulsion privately in the 1920s, remaining his own man to the end. The United States Army sent Goddard packing when he tried to interest them in his inventions in the early 1940s. EvenWernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun (1912-1977) started as the organizer of a private rocket society during the years of the Weimar Republic. The National Socialist regime quickly recruited as chief engineer of the Wehrmacht’s ballistic rocket program. (Below left to right: Tsiolkovsky, Goddard, von Braun)