A three-pillar war – part III

Sunday 22 April 2012

This is the third part of what has now become my weekly exploration of a part of the Second World War that was to develop into a long-running campaign called the Atlantic War.

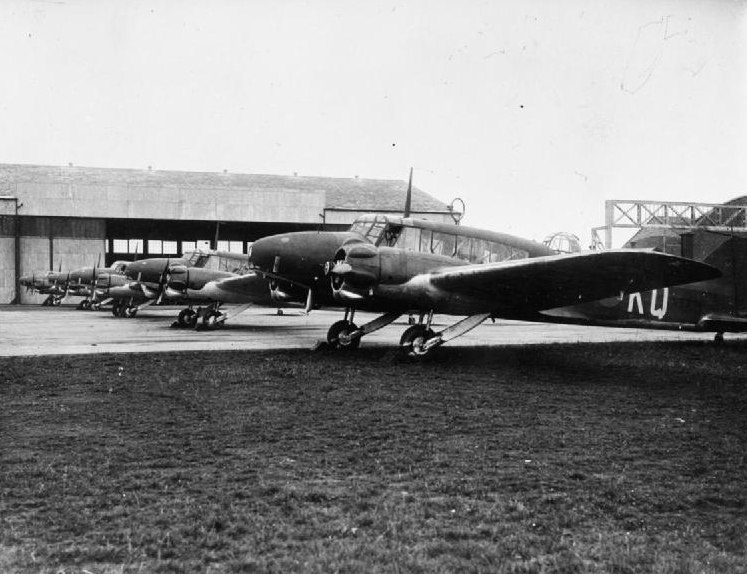

What has triggered this exploration is the recent availability of a substantial number of records from the National Archive online. This is, in my view, revolutionising the research process, as it enables a much more through analyses of these historic papers than, it would appear, have been hitherto afforded. The starting point for me was my book, The Many Not The Few, which sought to reintegrate what have been recorded in many contemporary histories as three separate episodes of the War, the Battle of Britain, the Blitz and the Atlantic War. My thesis is that these were all part of one larger battle, the strategic aim of which – on the part of the Germans – was to take Britain out of the war. One of the most significant points which emerged from my research for the book was the extent to which Winston Churchill was prepared to sacrifice the Atlantic convoys through the Battle of Britain period. The evidence has him robbing them of escorts in order to keep a fleet available to counter a German invasion, which he kept in port long after his advisors believed the threat had diminished or could be contained. This, I rehearsed in Part I but what I had not found out for the book was why, in the crucial months of September and October when losses were mounting to perilous levels, Churchill continued to insist that warships were retained on anti-invasion duties, going back on his world that they could be released. The answer to this came in Part II, with the newly available records showing that Churchill had become obsessed with the idea that the Germans, lacking either sea or air superiority, might mount a snap invasion using autumnal fogs in the Channel for cover, the barges being guided to their destinations by radio beams. Not only was this a fictional scenario, there was absolutely no evidence for it, and no intelligence that suggested it might happen, but nonetheless, it dominated Churchill's actions in the autumn of 1940. However, it was not only the warships that Churchill was keeping back. A potent weapon in the defence against the U-Boat was the aircraft, and from the very beginning RAF Coastal Command had mounted anti-submarine patrols into the Atlantic. But, at this stage in the war, its resources were pitifully inadequate. What is not fully appreciated, and rarely discussed, is just how pitiful these resources were. While much of the strength of Coastal Command was directed eastwards and to the Channel, at the end of August 1940, the effective strength devoted to shipping protection in the Atlantic amounted to precisely 71 aircraft. According to a secret report by the Naval Staff sent to the War Cabinet on 29 August, there was one flying boat squadron of six Sunderlands flying out of Oban, in Scotland (type pictured below), reinforced by three flying boats from Mountbatten, in Plymouth, and one flying boat from the Shetlands. There was also a flying boat squadron of six obsolete biplane Stranraers, appropriately flying out of Stranraer in Scotland (top). In terms of land-based aircraft, there was on squadron of 21 Ansons based at Aldergrove, temporarily reinforced by a further seven on detachment from Hooton Park on the Wirral, and 21 Hudsons on detachment from Leuchars. At Stornoway, there was a flight of six Ansons. That was it. With inadequate infrastructure to contend with, only so many additions could be accommodated, so the Naval Staff were fairly modest in its proposals. There asked that both the Hudsons and Ansons be replaced (pictured below, in same order). In the case of the Anson, this was especially urgent. The Mk1 had been introduced in 1936 and was already obsolete. Based on a civil passenger aircraft design, it had a patrol radius of 300 miles and a cruise speed of around 130 mph, its heaviest weapon being the 100lb bomb, to which U-Boats were impervious. Most desperately, the Admiralty wanted longer-range aircraft, asking for the Stranraers to be replaced with Sunderlands, for "more flying boats from America" and "shore-based reconnaissance aircraft using existing types such as Wellingtons or Whitleys. The most immediate effect could have been achieved by transferring Wellingtons or Whitleys from Bomber Command, where they were being used on the strategic bombing campaign in Northern Germany, to almost no effect at all. But it would have taken a directive from the highest level to have over-ridden the bomber. This was not to be. Churchill was equally obsessed with strategic bombing. Thus, on 30 August, when the War Cabinet met to consider the perilous state of merchant shipping, in response to the plea for the urgent provision of more patrol aircraft, the Chief of the Air Staff would only say that the Air Ministry would "do their best", but he could not promise anything in the near future. Churchill did not intervene. That "best" was indeed little. From October 1940, No. 502 (Ulster) Squadron was re-equipped with Whitley bombers, one of the least capable of the triumvirate of medium-range aircraft equipping the RAF, so underpowered that it could not maintain level flight on one engine. This had, on 4 November Admiral Pound, the First Sea Lord of the Admiralty interceding to call for the strengthening of Coastal Command. Amongst other duties, he noting that there was a need for continuous air cover for the new system of convoy organisation and additional reconnaissance in the convoy areas. He acknowledged that the strength had increase from 150 to 300 aircraft since 1939, but so had the tasks, including reconnaissance, anti-shipping strikes, minelaying and much else, including overseas commitments. Thus did Pound argue that the strength needed was "nearer to 1,000 planes in operation", even to the extent of keeping obsolete types in service rather than replacing them. By 20 November, a memorandum from the First Lord of the Admiralty, A V Alexander, was on the table. It followed a suggestion from the Minister of Air Production, Lord Beaverbrook, that the Admiralty should take over Coastal Command, after complaining of the poor state of serviceability of the Command, with eighty percent of the flying boats and sixty percent of the shore-based aircraft grounded through lack of maintenance. However, the memorandum brought the good news that the Air Ministry had recognised the need for urgent expansion and promised to deliver "as early as possible" four new squadrons. Thus formed on 21st November 1940 was No. 221 Squadron, the only one at the time to be equipped with Wellingtons (pictured, last shot, below), potentially giving Coastal Command an aircraft with double the patrol range of the Anson. The detail behind the experience of No. 221 Squadron, however, illustrates precisely the degree of priority given to protecting the convoys, with the squadron based at Bircham Newton in Norfolk, where it was to form and train. Rather than an operational squadron from the start, however, the crews had little experience of Wellingtons and some of the navigators, posted from Blenheims, had no long-range navigation experience. The few aircraft received came from Bomber Training Units, and were in very poor condition, requiring a great deal of work on them to make them operational. During December, January, February, the winter weather and shortage of aircraft prevented much flying, and when the squadron finally became operational on 23 February 1941, it went nowhere near the Atlantic. Instead, it relieved the Anson and Hudson squadrons escorting east coast convoys, and from March carried out moonlight and anti-shipping patrols around the Dutch coast. On 5 November, meantime, Churchill had asked the Admiralty and the Air Ministry to comment on Beaverbrook's proposal for a Naval take-over of Coastal Command. The Secretary of State for Air, Sir Archibald Sinclair, was the first to reply, on 21 November. Addressing Admiralty complaints, he wrote: "So far as I am aware", the only complaint is that it is not big enough. The Admiralty contribution, the next day, could not have been more contrary. A V Alexander wrote of five complaints. The Admiralty had no voice in the design and equipment of Coastal Command aircraft, nor any voice in the operational training. It had no responsibility for the day-to-day operational control of aircraft, and the numbers in Coastal Command were inadequate. Then, added Alexander, although the number of aircraft in Coastal Command is totally inadequate, the Air Ministry can under present arrangements deflect even the small force that exists from its naval purposes without even consulting the Admiralty. Thus, the reality of the Atlantic War by the end of 1940 was a system short of ships and aircraft, with the two operational services at loggerheads, all in a situation where, according to an analysis carried out in October 1940 by shipping minister Ronald Cross, we were set to lose the war. What is not always fully appreciated in that respect is that every ship sunk represented a cumulative loss. Not only was the cargo being carried at the time lost, but every future cargo. And, given that damaged ships were also being taken out of service awaiting repairs, the shipbuilding and repair yards could not restore lost capacity. By the third year of the war, with then current rates of shipping losses, imports were expected to fall from the 43.5 million tons in the first year to 32 million, less than was needed to keep the population supplied and sustain the war effort. Had not the US joined the war at the end of 1941, contributing its massive shipbuilding resources, and developing the inspired Liberty Ship programme, by the end of 1942 Britain could have been forced to sue for peace. By any account, therefore, this was part of the Battle of Britain, and it was not going well. And then, even the U-Boats were by no means the full extent of the problem. All things being well, we will have a look at the wider aspects of this war next week, then to look at the political implications, past and present, in the following week. COMMENT: "THREE PILLAR WAR" THREAD Richard North 22/04/2012 |

Booker on fractures

Sunday 22 April 2012

Illustrating the scope of the Booker column, we get one story about fracturing children's bones and another on fracturing rock in order to extract gas.

Bother are a mess, and after a while the messes start to merge into each other, as early readers found after the harassed sub inserted the wrong copy under the fracking headline. Such mistakes should not happen in a commercial enterprise, but the establishment has been reduced so much that such errors are bound to occur. Embarrassingly, the headline which had the wrong copy accused the greens of being "confused", but not as much as the newsdesk, which has unwittingly posted the children piece, and allowed comments. Such has allowed the usual quota of poison from the resident troll, while showing up others who have obviously commented on the headline without reading the text. Anyhow, the unconfused Booker is up top – click the pic to read it, and you will no longer be confused. COMMENT THREAD Richard North 22/04/2012 |

Come to the party

Saturday 21 April 2012

Following on from my earlier piece, in which reference was made to Peter Oborne and his so-called "insurgent" politicians, I've been taking a closer look at the last time we saw a significant move away from party politics.

This goes way back to 1942 and is discussed by historian Kevin Jefferys in his book, "The Churchill Coalition and Wartime Politics, 1940-1945", who observes that it had become a commonplace of political discussion during that period that the House of Commons was out of touch with public opinion. The result was a growing view that none of the existing parties could fulfil the wishes of the public. The most tangible evidence of this "movement away from party", however, writes Jeffreys, came with a three by-election victories for independent candidates in the first half of 1942, shortly after the disastrous fall of Singapore. The first of these was at Grantham on 25 March, where the official Conservative candidate was Air Chief Marshal Sir A Longmore. While he polled 11,391 votes, he was defeated by an independent candidate polling 11,758 votes, giving him the narrow majority of 367 votes on a forty-five percent turnout. The previous holder, Sir Victor Warrender, had polled 22,194 giving him a majority of 6,185. The winner, Denis Kendall, was the managing director of a munitions company, a man with a colourful history suspected by MI5 of harbouring Fascist sympathies. In his victory speech, he said: "I am not a party man. I am going to the House of Commons to tell them how to produce munitions". One of the reasons given for Kendall's success was "apathy and indifference", the Yorkshire Postrecording that "only" 23,000 people had voted out of an electorate of over 50,000. The Daily Express, on the other hand, thought his success a victory for those who "demanded urgency in the conduct of the war". Kendall was arguing that the war could be ended in 1942, with the opening of the second front. A slightly more comfortable lead was built up by the second of the independents William J Brown at the end of April. A well-known figure, Brown was then General Secretary of the Civil Service Clerical Association, and defeated the chairman of the local Conservative Association in Rugby. This seat had formerly been held by the now ennobled David Margesson, with a majority of 14,000 in 1931 and 7,000 in 1935. He had served both as Chamberlain's and Churchill's Chief Whip, a formidably powerful man in the corridors of Westminster but now with less reach in the streets of Rugby. "Men of action don't give the enemy comfort", had been Tory slogan and Margesson himself had weighed in on the hustings with the claim that a vote for the independent would satisfy only Hitler. Such were appeals to national unity, but they fell on deaf ears. Brown, campaigning on a platform which stressed his own hatred of the party machines, won by a "comfortable margin" of 679 votes. After the count, he declared: "I won because people are sick and tired of the party machines which took us into the war unprepared and have led us from disaster to disaster". Brown added: "The people have given me a message to Churchill that he should set himself free from the party prison and reassert individual responsibility in politics, and that he should put his foot down on privileged inefficiency in high places". On the same day an even more disturbing setback for the government occurred on Merseyside. There, a local journalist, George Reakes, had triumphed at Wallasey, where the previous Conservative holder, Colonel Moore-Brabazon, had won his seat with a majority of 14,458 over his Socialist opponent. In 1942, however, the local Tory organisation had been extremely weak and Reakes was able to win by 6,012 votes with the Conservative vote falling some 35 percent. After his victory had been announced, Reakes declared: "It is a victory for Churchill and our enemies will now know that Wallasey wants a vigorous prosecution of the war with a fight to the finish. The voters are dissatisfied with party politics". After the victories, the Daily Express was to observe that, "Mere symbols of unify do not satisfy the people any more as their representatives at Westminster", adding: "The people … are choosing the best man who seeks their support, independent of party". "If there is no comfort in the results for Hitler, there is no comfort for the party political machines either", it said. "The three constituencies were not 'doubtful' seats. They were Tory strongholds". The independents were elected, "because they expressed forcibly their belief that the war can be won in 1942. And because they will work to that end without the restrictions of the party system to hamper their endeavours". Here is a plain indication, the paper then said, "that the nation wants a halt called to the game of party politics. It is a most refreshing sign of healthy democracy in vigorous action! The Tory machine and the Socialist machine had better get in touch with the people if they seek to retain seats that come vacant". Years afterwards, it is Jeffreys who attempts to put these events in context, noting that the movement away from party was followed by a movement "back to party". However, despite Churchill's personal popularity, that drift did not go in his direction. It went to Labour, the party which seemed to have the ideas. Writes Jeffreys, the desire of the British people to create a better world, though imprecise in many ways, could not be mistaken. But Churchill and his senior colleagues had little faith in the "New Jerusalem". This, he says, was one of the things profoundly damaged the party. From this, we can make some cautious inferences. Firstly, sentiments can ebb and flow – because people are currently hostile to political parties does not mean they will always be. Second, people seem to be attracted to parties with the most positive ideas. Third, the vote does not necessarily go to the party with the most popular (or least unpopular) leader. But there again, we are talking about the past. Never in the field of party politics, one might say, have so few been loathed by so many, for so long. Things this time may be different. COMMENT: "SERMON OF THE MOUNT" THREAD |

Sunday, 22 April 2012

Posted by

Britannia Radio

at

14:30

![]()