| ||||

|

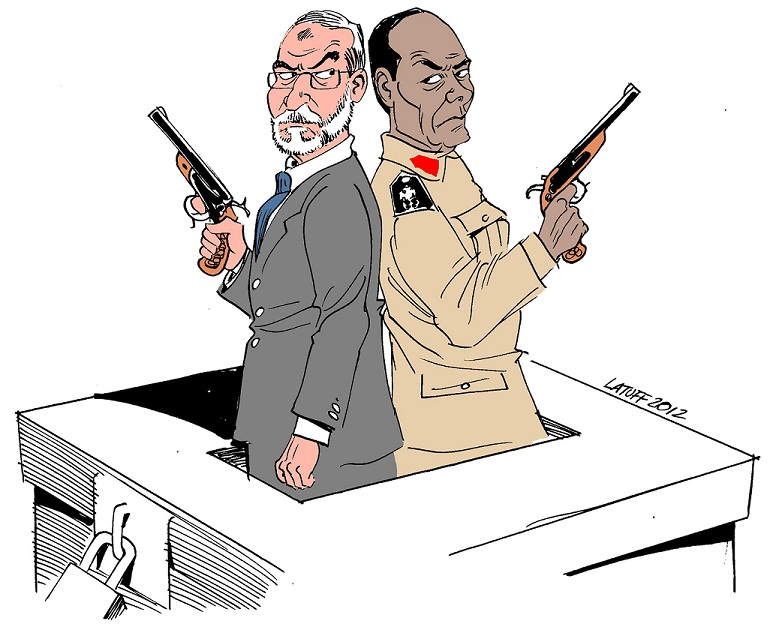

Inquiry & Analysis No. 865 The Egyptian Revolution Is Only Starting: Will Power Be Transferred From The SCAF To The Elected President And Parliament?By: Y. Carmon and L. Lavi* From a historical perspective, the Egyptian people's struggle against the authoritarian rule in the country is still in its early stages. On the face of it, the Egyptian revolution took place with the ousting of president Hosni Mubarak. However, in practice, most of the authorities remained in the hands of his associates, the members of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), headed by Field Marshal Muhammad Hussein Tantawi. The Egyptians' real struggle to realize the goals of the revolution, i.e., to transform the fundaments of the regime and transfer power from the military dictatorship to the elected president and parliament, is starting only now. Since winning the presidential election, Dr. Muhammad Mursi has found himself almost without powers, and he is currently seeking ways to consolidate his status as Egypt's ruler and to promote his agenda as far as possible. His first moves indicate that he does not intend to confront the SCAF at this stage, but to share power with it, and to acquire authorities through indirect manipulation rather than open conflict. In additional to the SCAF, which seeks to retain as many executive powers as possible, and Mursi, who has received a mandate to rule from the people and wishes to implement it, another powerful element in Egypt is the High Constitutional Court. Though this body is officially neutral, it is difficult to ignore the fact that its judges were appointed by the previous regime and that its rulings and their timing have tended to serve the SCAF, rather than Egypt's elected institutions. Mursi's attempts to assume executive powers have been hesitant, inconsistent and populist, and he has been quick to back down and cooperate with the dictates of the SCAF and the judiciary. The struggle to grant him more authority is being waged by the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) movement, which, unlike him, is not bound by protocol and can afford to confront the SCAF and the judiciary system; however, its struggle has also seen little success so far. As part of their struggle, Mursi and the MB are trying to protect the Constituent Assembly against attempts to dissolve the body, which is charged with the task of drafting Egypt's new constitution. This body is the last stronghold still left to the MB, and is highly important because it has the ability to make far-reaching changes and transform the power balance between the various branches of government.

What will be the nature of the struggle between the military dictatorship and the president and parliament? Will the SCAF give up its power without the people having to take to the streets again to fight for the realization of the revolution? Will the MB prefer to cooperate with the military authorities rather than confront them? The answers to these questions will be revealed in the coming months. This report reviews the efforts of the SCAF to strip the president and parliament of authority, and the efforts of Mursi and the MB to restore these powers. To read the full report, visit http://www.memri.org/report/en/0/0/0/0/0/0/6550.htm.

Inquiry & Analysis No. 864 Mursi's Ascension To Egyptian Presidency: Reactions In Arab, Muslim WorldBy: H. Varulkar* The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood (MB) and its braches around the Arab world rejoiced in the election of the MB candidate, Muhammad Mursi, as Egypt's new president. The MB celebrated his election as a victory for the movement and as a validation of the rightness of its struggle and its course, and drew encouragement for its future activity. This sentiment was largely shared by the Syrian opposition, which has been fighting Assad's regime for a year and a half, and saw Mursi's victory as heralding its own. Conversely, some of the Arab regimes in the Gulf, especially those of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which have long-standing ideological and political differences with the MB, viewed Musri's victory with considerable apprehension. Their chief concerns are that the Egyptian MB might try to export its revolution to their territory; that local MB activists in the Gulf may be encouraged by it; and that an MB-led Egypt may draw close to the resistance axis headed by Iran. In Saudi Arabia, these concerns were expressed in harsh articles against the MB in the local press. However, the Gulf states know that they need Egypt as a strategic ally and partner in leading the Arab world; hence, they are evidently trying to turn over a new leaf in their relations with the MB, in order to preserve the historical alliance with Egypt. Jordan, which for over a year and a half has seen a wave of protests by the MB-headed opposition in demand of reforms, likewise viewed Mursi's victory with concern, fearing an increase in the protests on its own soil and in the protesters' demands. King 'Abdallah hurried to take a series of measures to pacify the Jordanian MB, in a bid to prevent an exacerbation of the crisis between the movement and the regime. Qatar, which has used Al-Jazeera TV to encourage the Arab spring revolutions in the Middle East and especially in Egypt, and which is notable in its support of the MB, reacted to Mursi's election with exuberance. If, during the Mubarak era, Qatar competed with Egypt for leadership of the region, today, following the MB's victory, its press is celebrating Egypt's return to a position of regional dominance. As for the Iranian regime, it initially tried to persuade its public that MB-led Egypt was adopting the Islamic model of Iran, and hoped it would join Iran in an alliance against the Saudi-led Arab camp and the West. However, once it became clear that the Egyptian MB had no intention of emulating Iran or joining its axis, the Iranian press started to attack Mursi and present him as a collaborator with the West. To read the full report, visit http://www.memri.org/report/en/0/0/0/0/0/0/6549.htm. | |