Friday, 12 September 2008

London Banker

Ring Fences, Rustlers and a global bank insolvency

Although markets are global, and Lehman Brothers operations span the globe, all insolvency is local. The basic premise is that each jurisdiction buries its own dead and keeps whatever treasure or garbage it finds with the corpse. Local creditors get to recover their claims out of the locally available assets. If, and only if, there are any assets left over will international creditors be invited to make a claim for the rest. Europe has managed to harmonise cross-border insolvency for banks under directives and local law to embody principles of universality and unity within the EU, but that only works equitably if enough assets are in the EU when the bank fails, and local insolvency law still applies in all its divergent complexity.

Claims against a bank are deemed located wherever the contract creating the claim is undertaken. If it is under US law then the claimant must look to the liquidator in the United States and assets under his control for recovery. If the claim is in Hong Kong, then the claimant looks to the Hong Kong receiver and assets.

The key to having a happy insolvency, if such a thing exists, lies in ensuring that when a globalised bank goes bust, all the best assets are inside your borders and subject to seizure by your liquidators on behalf of your creditors. Everyone else outside your borders is on their own. As the US dollar is the reserve currency of banking and US Treasuries, Agencies and other assets are the highest preferred asset class, the US is almost always in a good position in an international bank failure.

The principle of using local assets for local recovery is known as the “ring fence” – the idea being that insolvency drops an invisible “ring fence” around any valuable assets at the borders to meet claims arising within the borders. No country is more assiduous in weaving the ring fence than the United States of America. It is a very successful strategy for US creditors. US creditors of failed international banks tend to recover disproportionately relative to creditors anywhere else. The ring fence contains all these choicest assets for US creditors, and all the international creditors are forced to pick among the dross of foreign assets to eke out a recovery, only receiving any residual US assets remaining after US creditors get 100 percent recovery.

Lehman has been deeply troubled and subject to speculation since the early spring. That was just about the time that we started to see a marked sell off in foreign markets where Lehman has long been a major player. Recently, along with intensification of that sell off, we have seen a strengthening of the US dollar and US asset markets.

If one were cynical, and one believed that Lehman was going to be allowed to fail pour encouragement les autres one might wonder if Lehman was quietly bidden – or even explicitly ordered – to sell off its foreign holdings and repatriate the proceeds to asset classes within the US ring fence. This would ensure that US creditors of Lehman received a satisfactory recovery at the expense of foreign creditors. It would also contribute to a nice pre-election illusion of a “flight to quality” as US dollar and assets strengthened on the direction of flow.

If one were really cynical, one might even think that a wily bank supervisor might arrange to ensure 100 percent recovery for its creditors with a bit of creative misappropriation thrown in the mix. Broker dealers normally hold securities and other assets in nominee name on behalf of their investor clients. Under modern market regulation, these nominee assets are supposed to be held separately from a firm’s own assets so that they can be protected in an insolvency and restored to the clients with minimal loss and inconvenience. Liberalisations and financial innovations have undermined the segregation principle by promoting much more intensive use of client assets for leverage (prime brokerage and margin lending) and alternative income streams (securities lending). As a result, it is often very difficult to discern in a failed broker who has the better claim to assets which were held to a client account but reused for finance and/or trading purposes. The main source of evidence is the books of the failed broker.

On the wholesale side, margin and collateralisation in connection with derivatives and securities finance arrangements mean that creditors under these arrangements should have good delivery and secure legal claims to assets provided under market standard agreements. As a result, preferred wholesale creditors could have been streamed the choicest assets under arrangements that will look above suspicion on review as being consistent with market best practice.

If Lehman were to go into insolvency, I will be interested to discover whether US creditors achieve a much higher proportion of recovery than their global peers in other locations where Lehman did business. If so, it will likely be because of the US ring fence and the months of repatriation of assets and funds back into the confines of the ring fence before the failure was finally orchestrated. It will also be because the choicest assets were preferentially delivered to preferred US creditors under market standard margin and collateral arrangements.

Unfortunately, the pace of an international insolvency means that any retrospective evaluation will be so far down the road that I will likely be almost alone in looking backwards to see what the final distribution effects are and what they mean for equitable principles of international banking practice.

Friday, 5 September 2008

Weaning the banks off the Old Lady's teat

There is a warm sense of security that comes from suckling liquidity from the teat of the central bank rather than foraging for capital and earnings in a harsh world full of threats and predators. Nonetheless, there comes a time when a good mother pushes away her importunate young and forces them to fend for themselves subject to her stern guidance and supervision.

Central banks have been suckling their broods of commercial banks since the credit crunch first exploded on the scene in August 2007. Now there are signs that the Bank of England and European Central Bank, at least, are keen to push their broods toward self-sufficiency, even at the risk that not all survive independently.

The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street has announced that she really, really means it when she says that the Special Liquidity Scheme introduced to enable banks to draw her gilts against mortgage-backed collateral will be closed down 20th October. The SLS was opened as a “one-off operation with a finite life” and was never intended to do more than bridge the liquidity gap created by the collapse of the mortgage-back securities market while banks adjusted their business models to changed market conditions.

The banks, led by UBS, are throwing temper tantrums, stamping their little feet, screaming in the financial press, but so far the Old Lady is holding firm. Mervyn King said last month:

"The SLS was introduced as a measure to deal with a legacy problem of liquidity of the stock of assets which banks owned last year when the crisis hit. So that window will close in October. The longer-term issue of tightening of credit conditions is much wider. That is to do with the health of the capital position of the banking system, and it's very important not to confuse the two".

Mr King’s determination to husband what remains of the Old Lady’s resources may have something to do with profligate abuse of them when opened to her brood. What started out as a scheme to extend up to £50 billion (a bit less than $100 million) in liquidity to shore up the UK credit markets during a surprise credit dislocation may have been drawn for as much as £200 billion in total as crunch turned to constriction. The Bank will only publish the true scale in October after the SLS closes. The SLS has been hungrily drained by banks keen to swap whatever unmarketable dross remained on their books for good central bank gilts.

The abuse has been made plain in numbers reported by the BIS.

Banks issued a record £45bn in mortgage-backed bonds in the three months to the end of June - more even than at the very height of the housing boom in 2006 - according to figures from the Bank for International Settlements. . . . . The Quarterly Review added: "Most of the UK issuance followed the Bank of England's announcement in April 2008 of a Special Liquidity Scheme (SLS) that enables UK banks to swap illiquid assets such as mortgage-backed securities against UK Treasury bills."

This record mortgage-backed issuance comes at a time when new mortgage lending in the UK has contracted very sharply, down 71 percent year on year for the month of July. That indicates a cynical abuse of the Old Lady’s generosity. Rather than be left with dry dugs dangling to her waist, the Old Lady would prefer to wean the banks while she retains ample bosom and sufficient other assets to shore up her public stature.

Over at the European Central Bank, a rule change this week will increase haircuts (discounts to stated market value) for collateral provided under that liquidity scheme from next February. The ECB has made available over EUR 367 billion (a bit less than $700 billion) under very liberal terms.

According the Financial Times:

The changes, which take effect from February 1, include increases in the average “haircuts” applied to asset-backed securities. A haircut is the amount deducted from the market value of a product when judging its value as collateral. In future, a blanket 12 per cent haircut will apply, replacing a previous sliding scale of between 2 per cent and 18 per cent. There will be penalties for asset-backed securities valued using models and for unsecured bank bonds.

Restrictions already in place on banks using assets they themselves had formed were extended to stop banks using assets from issues to which they had offered currency hedges or liquidity support above a certain level.

Analysts at Barclays Capital said the extra haircuts would mean banks might have to post an additional €25bn-€45bn of securities for collateral purposes. “That could cost €375m to €450m annually to banks ... Not insignificant, but probably bearable,” said Laurent Fransolet, analyst at Barcap.

The normally politic Yves Mersch made explicit reference in his remarks to "dangers of gaming the system".

Nonetheless, with house purchases falling to new lows and credit getting progressively tighter, the Labour government and the Council of Mortgage Lenders are wild to have another source of cheap liquidity if the Old Lady denies them. A new scheme for taxpayer-subsidised mortgage finance is in the offing. It is clearly bad public policy to have the government subsidise further borrowing for the housing sector after such a destructive bubble, but the scale of vested interest and the unpopularity of the Labour incumbents as the house prices fall make a new scheme a certainty all the same.

Rather like a mother who loves her young no matter how ill-bred, destructive and abusive they are to their peers or the community, the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street is unlikely to mind very much if British banks prosper by depredations on the politicians, taxpayers, market counterparties, corporate treasurers, hedge funds and others so long as they are out of the house. Having proved they have no sense of gratitude or duty to the Old Lady that preserved them in time of need, the others who will become their new targets can expect even less consideration.

Friday, 29 August 2008

Is the FDIC another troubled monoline?

As we all know, it is liquid reserves that enable a credit institution to cope with periods of uncertainty, underperformance and/or illiquidity. In the banking industry, the relationship between losses and reserves is referred to as the “coverage ratio” and it is a critical indicator of stress.

Those with too low reserves must borrow or recapitalise just at that point in the cycle when lenders and investors become wary sceptics as they contemplate the worsening business climate in general and deteriorating performance of the needy in particular. Those unable to secure credit or attract investment must look to official liquidity facilities, if available, and/or face forced asset liquidations and/or insolvency. Those who can secure credit or attract investment typically do so at a cost which impairs future profitability and so undermines future reserve growth (see From Capital-ist to Capital-less Economies).

It occurred to me to examine the coverage ratio in another context that I already planned to write about today: the FDIC.

For the past month or so, I haven’t been able to look at the FDIC without seeing a big, undercapitalised, monoline insurer. I didn’t want to see the FDIC that way, especially since Mervyn King, governor of the Bank of England and normally a very sensible bloke, is a huge admirer of the US deposit insurance system and wants to import FDIC principles here to the UK. If the FDIC is fundamentally flawed, then the UK may once again follow the US over yet another cliff with too little reflection of our inherent self-interest in avoiding yet another public policy disaster.

Facing my fears, as we all should if we aspire to be rational and make superior judgements, requires assessing the facts.

The following excerpt from Wikipedia describes the characteristics of a monoline insurer:

Monoline insurers (also referred to as "monoline insurance companies" or simply "monolines") guarantee the timely repayment of bond principal and interest when an issuer defaults. They are so named because they provide services to only one industry.

The economic value of bond insurance to the governmental unit, agency, or company offering bonds is a saving in interest costs reflecting the difference in yield on an insured bond from that on the same bond if uninsured.

So what is the FDIC then? The FDIC “guarantee[s] the timely repayment of [deposits] when a[n insured financial institution] defaults.” The FDIC “provide[s] services to only one industry. The economic value of [FDIC deposit insurance] to the [insured banks] offering [deposit accounts and certificates of deposit] is a saving in interest costs reflecting the difference in yield on an insured [deposit] from that on the same [deposit] if uninsured.”

The similarities are too great. The FDIC is a monoline insurer in all the ways that matter.

Taking that as a starting point then, what makes the FDIC better able to withstand the rigours of a financial crisis than its private sector monoline brethren? Let’s look at the advantages the FDIC has over lesser monolines.

Regulatory Powers: The FDIC has the power to compel banks to increase their capital, limit their riskier business activity, and otherwise intervene to curb management’s rush toward bank failure.

Mandatory Participation: American banks have no choice but to buy their deposit insurance from the FDIC, and are obligated to do so. They have no choice but to pay the premia assessed by the FDIC when due if they want to remain in business. With more than 6,000 banks participating, the risks should be diversified (except, of course, that banks are herd animals so that risk outcomes are highly correlated for the sector as a whole). Risk-Weighted Premia: Theoretically, the FDIC’s risk-based CAMELS rating system should require riskier banks to pay more. It would be interesting to apply rigorous market backtesting methodologies to see whether CAMELS is performing as expected in this downturn, or whether like so much else, CAMELS has been distorted by forbearance and crony capitalism into another tool for industry concentration and selective competitive advantage favouring well-connected big banks during the M&A boom years.

Statutory Receiver of Failed Banks: When a bank fails, the FDIC takes over the assets and liabilities, and is able to rapidly arrange for bridge banks, purchase and assumption transactions to healthy banks, and otherwise realise value from failed banks while minimising systemic disruption to retail and commercial account holders. This is a critical function as the surest way to prevent draws of deposit insurance is to compel a work out that secures depositors unimpaired access to their accounts.

Treasury Credit as a Backstop: If it runs into trouble, the FDIC can borrow from the Treasury (just like everyone else in corporate America, it seems).

This is a formidable armory of powers and privileges. And we know the FDIC is experienced at using its powers to good effect, having proven itself several times through the past 75 years. Nonetheless, these powers may be insufficient if the scale of losses insured by the FDIC overwhelm the capitalisation of the insured banks and the resources of the FDIC.

This is where Reggie’s test of losses relative to reserve growth becomes a telling indicator of future problems.

Looking at the most recent Quarterly Banking Profile from the FDIC, we see an ugly picture:

Net Charge-Off Rate Rises to Highest Level Since 1991

Loan losses registered a sizable jump in the second quarter, as loss rates on real estate loans increased sharply at many large lenders. Net charge-offs of loans and leases totaled $26.4 billion in the second quarter, almost triple the $8.9 billion that was charged off in the second quarter of 2007. The annualized net charge-off rate in the second quarter was 1.32 percent, compared to 0.49 percent a year earlier. This is the highest quarterly charge-off rate for the industry since the fourth quarter of 1991. At institutions with more than $1 billion in assets, the average charge-off rate in the second quarter was 1.46 percent, more than three times the 0.44 percent average for institutions with less than $1 billion in assets.

Note that big banks – those presumably with favourable CAMELS ratings in years past, allowing them to gobble up their less favourably rated peers – have much worse charge-offs than smaller banks.

Large Boost in Reserves Does Not Quite Keep Pace with Noncurrent Loans

For the third consecutive quarter, insured institutions added almost twice as much in loan-loss provisions to their reserves for losses as they charged-off for bad loans. Provisions exceeded charge-offs by $23.8 billion in the second quarter, and industry reserves rose by $23.1 billion (19.1 percent). The industry's ratio of reserves to total loans and leases increased from 1.52 percent to 1.80 percent, its highest level since the middle of 1996. However, for the ninth consecutive quarter, increases in noncurrent loans surpassed growth in reserves, and the industry's "coverage ratio" fell very slightly, from 88.9 cents in reserves for every $1.00 in noncurrent loans, to 88.5 cents, a 15-year low for the ratio.

I had to smile at the heading. The clumsy phrasing of “Does Not Quite Keep Pace” has been carefully drafted in preference to the less wordy but more apt “Lags”.

The bottom line is that the “coverage ratio” is worsening for the FDIC flock, and the coverage ratio for the FDIC is not looking too healthy either. At the end of the second quarter, the FDIC reserve fund was down to a mere $45.2 billion after just 9 bank failures this year. While it does not publish a coverage ratio in respect of itself, IndyMac alone will require an estimated $8.9 billion of FDIC reserves to resolve, almost twenty percent of remaining reserves. The FDIC intends to raise reserves through a premium increase in October, but a lot can happen in two months in these febrile times.

So the FDIC may well become yet another troubled monoline insurer. Indeed, Sheila Bair, serial forbearance artiste chairman of the FDIC (formerly a Treasury official and Republican congressional aide), conceded as much when she raised the possibility this week that the FDIC might be joining the queue for a Treasury hand out to see it through short term liquidity problems.

"I would not rule out the possibility that at some point we may need to tap into [short-term] lines of credit with the Treasury for working capital, not to cover our losses," Bair said in an interview.

The FDIC is too critical to the fabric of the US banking system to become another monoline casualty of the forbearance backlash crippling the banking industry. If there ever was a case for “systemic risk” deserving a bailout, the FDIC would get my vote (and presumably every Congressman’s too). But an FDIC bailout would be yet another signal to international creditors of America that the financial methods and models so widely exported and extolled over the past quarter century were fundamentally misguided and dangerous.

If the FDIC model fails, then what are the alternatives for deposit insurance? An intriguing idea floated in the Financial Times a couple weeks ago was to partially privatise deposit insurance through the excess liability reinsurance markets, allowing Warren Buffett to run his sliderule over the regulatory and risk management profile of banks to set a market price for insuring a failure.

Excess liability insurance would spread deposit insurance risk beyond the UK banking sector to global catastrophe insurance markets, reducing the pro-cyclical liquidity impact of any deposit insurance claim. In normal circumstances it should cover the risk of a large UK bank failure at a cost well below pre-funding, particularly in upswings of the economic cycle, while spreading the costs in a managed way if claims are sustained during downswings. Periodic tendering would ensure that market pricing reinforces discipline in the banking sector toward better management throughout the business cycle, co-operation on rescues of troubled banks and efficient resolution processes. The capital efficiency of these flexible arrangements should give UK banks a competitive edge.

In globalised markets, with globalised banks, perhaps globalised deposit insurance through excess liability insurance and/or catastrophe bond finance is not such a bad option. It may not be popular, however, with the crony capitalists and their political clientele who prefer the cheaper option of socialising losses via the Treasury to taxpayers and global public creditors, but at least it’s an alternative to the US model for the UK and others to consider.

Thursday, 28 August 2008

China Threatens to Raze the House of Cards

Freddie, Fannie Failure Could Be World `Catastrophe,' Yu Says

"If the U.S. government allows Fannie and Freddie to fail and international investors are not compensated adequately, the consequences will be catastrophic,'' Yu said in e-mailed answers to questions yesterday. "If it is not the end of the world, it is the end of the current international financial system.''

"The seriousness of such failures could be beyond the stretch of people's imagination,'' said Yu, a professor at the Institute of World Economics & Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing. Yu is "influential'' among government officials and investors and has discussed economic issues with Premier Wen Jiabao this year.

And from this morning's Financial Times:

Bank of China flees Fannie-Freddie

Bank of China has cut its portfolio of securities issued or guaranteed by troubled US mortgage financiers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by a quarter since the end of June. The sale by China’s fourth largest commercial bank, which reduced its holdings of so-called agency debt by $4.6bn, is a sign of nervousness among foreign buyers of Fannie and Freddie’s bonds and guaranteed securities. Asian investors, in particular, have become net sellers of agency debt, said analysts. However after a sharp drop in their market value last week, Fannie and Freddie have made a strong recovery after successful short-term debt sales. Fannie was 13.5% higher on Thursday and Freddie was up 12%. Bank of China’s disclosure on its holdings of Fannie and Freddie securities came as the bank reported a 15% increase in Q2 profit.

Sunday, 24 August 2008

Quotable: Mandela, Biko and Tutu

"The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed." - Steven Biko

“We may be surprised at the people we find in heaven. God has a soft spot for sinners. His standards are quite low.” - Bishop Desmond Tutu

A Better Bill of Rights

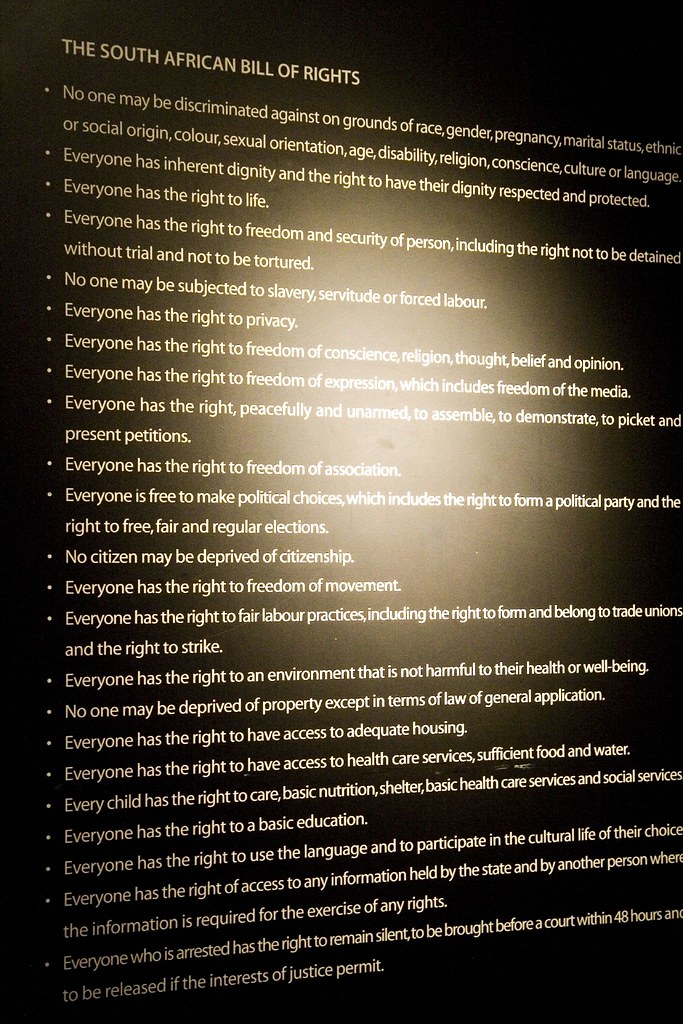

At the Apartheid Museum yesterday morning, I saw a summary of the terms of the South African Bill of Rights. We have no equivalent here in the United Kingdom. I envy the South Africans for having such a clear, unequivocal statement on the limits of government power to discriminate or oppress.

The summary in the Apartheid Museum pictured above reads as follows:

The South African Bill of Rights

• No one may be discriminated against on grounds of race, gender, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, culture or language.

• Everyone has inherent dignity and the right to have their dignity respected and protected.

• Everyone has the right to life.

• Everyone has the right to freedom and security of person, including the right not to be detained without trial and not to be tortured.

• No one may be subjected to slavery, servitude or forced labour.

• Everyone has the right to privacy.

• Everyone has the right to freedom of conscience, religion, thought, belief and opinion.

• Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, which includes freedom of the media.

• Everyone has the right, peacefully and unarmed, to assemble, to demonstrate, to picket and present petitions.

• Everyone has the right to freedom of association.

• Everyone is free to make political choices, which includes the right to form a political party and the right to free, fair and regular elections.

• No citizen may be deprived of citizenship.

• Everyone has the right to freedom of movement.

• Everyone has the right to fair labour practices, including the right to form and belong to trade unions and the right to strike.

• Everyone has the right to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being.

• No one may be deprived of property except in terms of law of general application.

• Everyone has the right to have access to adequate housing.

• Everyone has the right to have access to health care services, sufficient food and water.

• Every child has the right to care, basic nutrition, shelter, basic health care services and social services.

• Everyone has the right to a basic education.

• Everyone has the right to use the language and to participate in the cultural life of their choice.

• Everyone has the right of access to any information held by the state and by another person where the information is required for the exercise of any rights.

• Everyone who is arrested has the right to remain silent, to be brought before a court within 48 hours and to be released if the interests of justice permit.

The South African Bill of Rights sets the high mark we should all aim for in reforming relations between the people and the state, fighting back against the derogations of civil liberties forced through in consequence of the manufactured and hyped hysteria of the war on terror. Violence, no matter in what form or from what source, should never be the justification for relaxing our vigilence in preserving our rights or our principles.

In this context, one uncomfortable fact I learned in the Apartheid Museum was that it was the British that innovated concentration camps. In the actions to clear South Africa of Boers from 1900 to 1902 they rounded up whole Boer families and kept them in concentration camps. I had thought it was a joint German-Turkish innovation for the Armenian genocide, but it appears the British led in the ethnic cleansing stakes early in the last century.

Go read the South African Bill of Rights - especially if you are a lawyer.

Hat tip to NYCviaRachel on Flickr for the great photo of the Bill of Rights summary at the Apartheid Museum. My picture wasn't clear enough.

Friday, 22 August 2008

Optimism in Dubai and Johannesburg

First, Dubai. I never cease to be amazed by this city. Having very little oil, Sheikh Mohammed and his predecessors chose to use Dubai’s historic advantage as a trading port as the basis of growth and development. Having achieved world class status as a port, tourism hub, commodities trading hub, trans-shipment hub, technology/communications hub, and finance hub, the latest ambitions are to drive development as a centre of excellence for higher education and medical treatment – and then a space programme.

I would never, never bet against Sheikh Mohammed. I’m not sure he isn’t more successful at investing than Warren Buffett, were a dollar for dollar comparison of returns possible. Unlike Warren Buffett, the Sheikh does not invest in equity of companies with proven management, but creates whole companies and industries from scratch by driving high achievement throughout the Emirati community which he educates and appoints to managerial positions, and through attracting the best business talent globally. Dubai’s scale, sophistication and prosperity are proof he understands both leverage and results-driven management.

Is Dubai a bubble economy? Of course it is, but even when the bubble bursts the accomplishments and dynamic commercial skills concentrated in Dubai will persist and form a solid foundation for enabling future growth. My guess is that as the US and UK financial-based economies implode from debt-deflation, and their military influence in the Gulf recedes, Dubai will strengthen its network of trade and finance deeper into former Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa. Dubai will facilitate the investment capital flows that allow all of these diverse geographies to develop according to their internal political, economic and resource constraints.

A word about cronyism and the difference between the USA and Dubai. In the US the well connected can fail upward, with friends covering for them and promoting them and financing them to new ventures. George W. Bush’s whole miserable business career and cronyist administration of failed Nixonites is proof of that. In Dubai, you don’t fail because it would shame your family. I have seen young Emerati with no background in the businesses they were appointed to mature rapidly into good managers because the massive pressure of family and social connections demands that they not screw up when given an opportunity to perform.

The reward for good work is more good work, and Sheikh Mohammed only promotes those who have proven adept at managing the opportunities formerly provided to them. Being a small country that loves to gossip, he stays very well informed. Those who choose to be corrupt, lazy, selfish and self-aggrandising are given enough commercial rope to hang themselves, and then obligingly hung (metaphorically) as an example to others. Those who are diligent, professional, ambitious and productive are promoted, also as an example to others. Families gain status by producing good executives, reinforcing a family interest in educating and motivating their young. Those who fail can go into business for themselves, as there is no shortage of opportunity, and that saves the emirate underwriting their risks while it gains from new enterprise. I suspect the recent investigations of corruption at real estate and finance companies are based on good evidence, but the subtext of the very public inquiry is a warning to every manager in Dubai to remember that they owe their success and their loyalty to the leadership, family and community that put them in their current positions.

I once heard of Franklin Delano Roosevelt that in his administration, he owned the successes and the appointees owned the failures. That seems to me to be a reasonable way to motivate innovation and infrastructure development. It doesn’t fit with the bonus-centric incentive programmes so beloved of modern boardrooms and management consultancies, but as a means of engineering social prosperity through government programmes, it might have merits. FDR would not have renewed massive no-bid contracts with Halliburton’s KBR and others once they failed to deliver essential goods and services to wartime troops in a combat zone. FDR would not have appointed the delusional and incompetent Defense Undersecretary Paul Wolfowitz as president of the World Bank. Times have changed.

Perhaps Halliburton in Dubai will corrupt Dubai, or perhaps Dubai will reform Halliburton. Since Halliburton is moving its global headquarters to Dubai to evade US taxes, investigations and subpoenas, we will have the chance to find out.

Now to Johannesburg, where I stay in as comfortable a hotel as anywhere I’ve been. I drink the tap water – that says a lot in Africa. The food is excellent, with springbok shank and kudu steak new favourites.

I have been here every two years since 2004. Each time I am impressed with the rapid progress. There are problems, sure, but there are problems everywhere. The electricity grid failures in the early part of this year were a wake up call that the government needs to focus on the basics of infrastructure if it is to continue to provide growth and jobs to the vast population. Unemployment remains stubbornly high, at almost 40 percent. The refugees who have fled to South Africa from neighbouring Zimbabwe, add to the pressures (and explain why stabilising Zimbabwe is more important to the Mbeki government than confronting the egregious Mugabe).

When I first visited in 2004 there were still vast shantytowns around the capital. When I next visited in 2006 these had been largely replaced with neat little tract houses, each with plumbing and electricity. Now the housing boom is slowing, credit is tightening, but millions have homes they did not have before. That is a major achievement. Unlike America where huge houses are the norm, here the norm is much more modest and sustainable.

On learning I was in banking, my driver from the airport handed me an e-mail he had received quoting John Mauldin’s recent praise of South Africa:

Johannesburg is a world-class city, on a par with New York or London or any major city in terms of facilities, shops, infrastructure... and traffic. There were new shopping malls all over, and the stores were busy. The restaurants were excellent. The hotels I stayed in and spoke at were excellent and modern. The Sandton area is particularly pleasant.

Durban is a tropical jewel on the Indian Ocean. Again, there was construction everywhere - a green, verdant city of 1,000,000 people, with modern roads and great weather.

I have been to Sydney, Vancouver, and San Francisco. I love all of them. But for my money, Cape Town is the most beautiful city I have been to in the world. Amazing mountains, blue water harbours, white sand beaches, with wineries nestled in among the mountains and valleys. The Waterfront area, where I stayed, is fun and vibrant. Again, an amazing amount of construction everywhere, especially in the waterfront area, as investors from Dubai are pouring huge sums of money into creating a massive residential/business/ retail/restaurant development. There are several similar, quite large developments going up in different parts of Cape Town.

. . .

The simple fact is that as the world grows more prosperous we are going to need more grain and other foods. Where is the land we are going to need to feed the world? There is an abundance in Africa, along with the needed water and labour. And as African countries upgrade their infrastructure, it will improve the ability of farmers to get their grains to market at profitable levels.

There is much to like about emerging markets. That is where a great deal of the real potential growth in the coming decades will be. And South Africa will be one of the better stories. If you are not doing business there already, you should ask yourself, why not?

Mauldin offers specific praise for development of South Africa’s housing, retail, banking, commodities and farming sectors. I have never read a piece by him so optimistic about anywhere else, particularly in the developing world.

I thanked my driver for the Mauldin article, but suggested that the problems in the banking sector would cause problems for South Africa too. My driver then proceeded to detail his own preparations for a downturn in the economy: selling his old passenger van to pay off the newer one; paying off all his credit cards and keeping the balance at zero each month; delaying his purchase of a new house for at least a year while he sees what happens in property. This lone tour driver was more prepared for a shift in the economy than most of the bankers in the City of London. And if he reads John Mauldin, he is better informed too.

The group of bankers which showed up the next day for my workshop was another pleasant surprise. In 2004 the group was widely mixed as to backgrounds, race and abilities. In 2006 it was whiter and more professional, but also less friendly. In 2008 the group is blacker, more professional still, more experienced, more knowledgeable and universally friendly too. They are delightful to teach as they know enough to take in information readily and apply it to their careers and specialties. They collaborate readily, with clear trust and confidence in each other. Everyone is respectful and considerate.

I asked some neutrally each break about the challenges in South Africa, and they were uniformly optimistic. This is a big contrast to 2006, when the group complained about racial quotas, reforms and problems much more. One expressed concern about the potential damage of a corrupt government when Zuma takes over from Mbeki, and the others all nodded, but then he confirmed that the direction of change for the present remained for the better, and that it would take time to reform the ANC.

I have always believed that democracy can only really exist in those states with a large middle class. I do not subscribe to the view that democracy should be universal, as poor or rich are too self-interested to allow uncorrupted democratic government unless constrained by a middle class from abuses. As South Africa continues to grow at 4-5 percent each year (probably an under-estimate of real growth), the middle class continues to grow and prosper. So although a Zuma administration may hold risks, I hope there will be constraints on their policies as the already substantial and growing middle class enforces longer term discipline on the government.

I could not live in Dubai, but for the first time, I find myself looking around me and thinking I could live in South Africa. That says more about the optimism I feel here than any statistics.