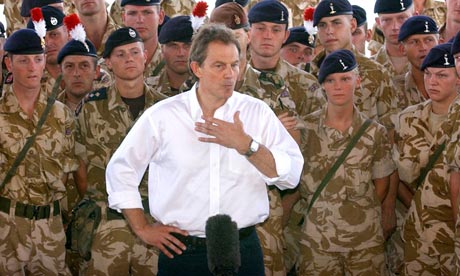

Evidence details ignorance, hasty plans and a one-sided relationship with the US Tony Blair addresses British troops in Basra,.southern Iraq in 2003. Photograph: Reuters Some will always believe that Tony Blair took the country to war in Iraq on a lie, but the most damning charge emerging from the Iraq war inquiry so far is that Britain went to war on a wing and a prayer. The main charges, after four weeks of cross examination, are that Britain had minimal influence over American diplomatic and military strategy, did not plan correctly for the aftermath of war, and utterly misconstrued post-war Iraqi society. It is these charges as much as whether intelligence was doctored that are likely to make the Labour political class squirm when they give evidence to the Chilcot inquiry starting in January. The chronology to disaster that has seeped from the inquiry makes sometimes shocking reading. It is after all the first time the British diplomatic and military establishment have had to discuss openly their secretive relationship with the US in the run-up to the war. The diplomats have been freed to disclose their distaste for the simplicities of the neo-cons in Washington, their limited entry points into Washington bureaucratic in-fighting and their shuffling admission that they went to war knowing the aftermath was unplanned – a "known unknown" in the immortal words of US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld, one of the villains of this inquiry so far. Yet what has emerged already from the 12 sessions with British defence, intelligence and diplomatic officials is the extent to which Britain seemed to slide into war, ultimately with little Whitehall resistance. The inquiry has also shown the extent to which Whitehall went to war ignorant of Iraq's near economic collapse, or the risks of a Sunni-Shia civil war. On the basis of the evidence given so far, these are the key questions the political class will have to answer: • Did Tony Blair and the cabinet gradually commit itself to regime change in Iraq and always know they would join the war if UN support was not forthcoming? Almost all the evidence from the military insists that British joint planning with the Americans was contingent on political endorsement, and the backing of the UN. Yet former ambassador Sir Christopher Meyer claims that Blair committed himself intellectually to regime change. • Did Blair give the defence ministry conditional permission to prepare for war at a secret meeting in Chequers the weekend prior to meet George Bush at his ranch in Crawford in April 2002? • Should Britain in March 2003 have withdrawn its support for the war after the failure to secure a second UN resolution giving Saddam a final chance to comply? Edward Chaplin, Foreign Office director for the Middle East, claimed he persistently flagged up that an invasion without UN support would lack legitimacy, as opposed to being unlawful. • Did Britain plan for the aftermath properly? Lieutenant General Sir Freddie Viggers, the chief British military representative in Baghdad after the war, told the inquiry: "We suffered from the lack of any real understanding of the state of that country post-invasion. We had not done enough research, planning, into …the country coming out of 30 years of the Ba'athist regime, the dynamics of the country, the cultures, the friction points between Sunni, Shia and Kurd." SIr Peter Ricketts, the foreign office political director said " I think they (the Americans) had a touching faith that, once Iraq had been liberated from the terrible tyranny of Saddam Hussein, everyone would be grateful". Sir David Manning admitted " I think the assumption that the Americans would have a coherent plan which would be implemented after the war was over obviously proved to be unfounded. There was confusion over this. • Was Whitehall geared up for war? Whitehall realised that Rumsfeld had won a turf war with the state department on post-war planning, and no plans were in place. Hastily the UK set up an Iraq Planning Unit on 10 February 2003 with fewer than 10 staff. Major General Tim Cross, the only UK military official appointed to help plan the invasion aftermath told the inquiry the unit "suffered from chaos, lack of planning and a chorus of competing voices." Apart from that an ad hoc committee of civil servants with a cabinet office secretariat met ahead of the war, but at junior level . No Iraq cabinet committee existed and according to Cross "I got no sense at all cross Whitehall that there was any coherence in a single pan Whitehall perspective on what this was all about." But Desmond Bowen, deputy head of Overseas and Defence Secretariat admitted was there a moment when the OD secretariat put up its hand collectively and said 'you know you should stop and think'. I dont think I can say that was the case" . Once the war began Bowen said "There was no formal ministerial group. It was run out of Number 10 and there were ministerial meetings, with what frequency exactly I don't know. Viggers complained " There were lots of plugs and lots of sockets, but not too many of them were joined up. Without a single minister to drive it forward it was very difficult to get the officiala to focus on the whole" . • Did the Treasury not commit the resources for the reconstruction ? Chaplin said: "If you have a decent plan and an idea of what you are aiming for, you need to identify the resources necessary to carry that out. It was certainly one of the constraints in the early months – seeing the need for additional expertise but not having the mechanisms to identify, train and dispatch those people quickly enough." • Did Britain stumble into running Basra and the south-east? Successive witnesses have said Britain did not want to run southern Iraq partly because of the potential cost and fears that the absence of a full UN mandate made the occupation illegal. Sir Nigel Sheinwald, Blair'sforeign policy adviser from August 2003, said: "We had no plan for handling Basra because that was something that only emerged during the course of the military action." • Did the Department for International Development (Dfid) refuse to participate? Lt General Sir Robert Fry, deputy chief of joint operations, said: "I think we had the Dfid representatives who came to the Permanent Joint HQ who would hardly conceal their moral disdain for what we were about to embark upon." • Should Britain have worked harder to stop the American Coalition provisional authority chief, Paul Bremer, going ahead with "de-Ba'athification" of the Iraqi army and civil service in the summer of 2003? Viggers described the decision as "crazy". Manning said: "I'm not aware of anybody in London, either an official, myself or at ministerial level, who thought that disbanding the army or having a purge of the Ba'ath party was a good idea". • Did Britain overestimate its influence on the US? Dominic Asquith, former British ambassador to Baghdad, said: "I think there was an unrealistic expectation among our political leaders of the degree to which the Americans would absorb and act upon our advice." Admiral Lord Boyce, the former chief of defence staff, said "I could not get across to the US the fact that the coalition would not be seen as a liberation force and that flowers would be stuck at the end of rifles and that they would be welcomed and it would all be lovely."Iraq inquiry reveals chaos that led Britain to war

Friday, 25 December 2009

Posted by

Britannia Radio

at

09:01

![]()