Best wishes to all for the Jewish and British years as well as the Scottish.

The Kingdom of Strath- Clyde (Cluyd or Lluyd) was an ancient British, Welsh-speaking area until the 11th century that the 'Scots' seemed to have forgotten.

The Picts were separate to the north. William Wallace (Walsh) was probably of the Welsh heritage!

See for example http://earlymedievalgovan.wordpress.com/2012/01/05/people-place-memory/

So much for remembering old acquaintances!!

Heart of the Kingdom

Early Medieval Govan

People, Place & Memory

January 5, 2012 by Tim

In the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries, when the sculptured stones now preserved in the old parish church at Govan were being carved, the people of the area spoke a language similar to Welsh. This differed from the Gaelic of Ireland and Argyll, having more in common with the language of the Picts to which it was closely related. But the district around Govan was not Pictish. Its inhabitants in early medieval times were not Picts but Britons. They were descended from natives encountered by Roman armies during the invasion and conquest of Britain in the 1st century AD. The Romans used the name ‘Britons’ as an umbrella term encompassing all indigenous people of the island. Later, at the end of the 3rd century, another term Picti came into use to describe troublesome groups of Britons in the highland zone beyond the Forth-Clyde isthmus. Meanwhile, in the far northwestern coastlands, native communities in Argyll and the Hebrides adopted the Gaelic speech of Ireland and, by c.300, were no longer identifiable as ‘Britons’. These groups became known as Scotti(Scots), a name apparently bestowed by Rome on all Gaelic-speakers regardless of where they lived.

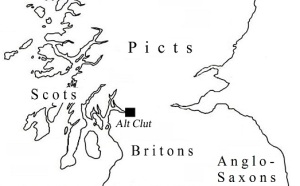

A different group of people, the Anglo-Saxons or ‘English’, came to Britain to fight for the Roman Army as mercenaries. After the collapse of Roman rule in the early 5th century they arrived in greater numbers, sailing across the North Sea from homelands in Germany, Denmark and Holland. Within two hundred years they had taken over many southern parts of Britain, seizing territory by force and establishing their own kingdoms. By c.700 only a few western areas remained in the hands of the Britons, the largest block comprising what is now Wales. In the North, the last independent kingdom of Britons lay in the lower valley of the River Clyde. Its main centre of power was Alt Clut, the Rock of Clyde at present-day Dumbarton. From this lofty citadel the kings of Alt Clut looked out on a realm surrounded on all sides by enemies: Scots to the west, Picts to the north, Anglo-Saxons to the east and south.

The Britons of the Clyde were converted to Christianity in the 5th and 6th centuries. Missionaries from other parts of Britain, and from Ireland, preached among them and baptised the kings of Alt Clut. Old legends and traditions assert that the earliest churches were founded by saints such as Kentigern (Glasgow), Conval (Inchinnan) and Mirin or Mirren (Paisley). The first church at Govan is said to have been established by St Constantine, an obscure figure identified in later tradition as a disciple of Kentigern. More will be said of Constantine in a future blogpost.

The kingdom of Alt Clut was still in existence when the Vikings began raiding the British Isles at the end of the 8th century. In 870, a large Viking army from Dublin besieged the royal citadel on Clyde Rock and captured the king of the Britons. It is sometimes assumed that this led to the total collapse of the kingdom, and that it was seized by the Scots, but this is not what happened. The focus of royal power simply moved upstream, away from the Rock of Clyde. One new centre of royal authority began to develop on the south bank of the river, at an ancient crossing-point opposite the inflow of the Kelvin. Here, at Govan, and at other places along the valley, the old realm of the Clyde Britons rose again with renewed vitality. The kingdom received a new name, Strat Clut(Strathclyde) to show that its heartland was now the valley of the river rather than the headwaters of the firth. From here the kings of the Britons began to take back what they had lost. Their reconquest was swift, for their former foes in the Anglo-Saxon realm of Northumbria had already been ousted by Viking warlords. The rule of Northumbrian kings no longer reached across the Solway Firth as it had done in the 7th and 8th centuries. By the early 900s, the kings of Strathclyde held sway over large tracts of what is now South West Scotland, having ousted an English-speaking aristocracy from lands that had been Northumbrian for the previous two hundred years.

Within a couple of generations of the siege of Dumbarton the power of the Britons reached as far south as the River Eamont in present-day Cumbria. The latter has been a familiar name on modern maps since 1974 when the old counties of Cumberland and Westmorland were amalgamated but its origins are much older. It is a Latinised form of Old English Cumber Land (‘Land of the Cumbri’), a name we find in the 10th-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Cumbri is simply a northern equivalent of Cymry (pronounced ‘Cum-ree’), a term still used today by the people of Wales when referring to themselves. Both terms derive from an older word combrogi which meant ‘fellow-countrymen’ in the ancient language of the Britons. The kings of Strathclyde, together with their subjects at Govan and elsewhere, considered themselves Cumbri, but to their Anglo-Saxon neighbours they were simply wealas (‘Welsh’) like their compatriots further south.

Strathclyde remained a major political power to the end of the 10th century and was still playing an important role in the early 11th. Its kings took part in significant wars and in many other great events of the time. This was the period when the stonecarvers of the ‘Govan School’ produced the crosses, cross-slabs and hogback tombstones that we see today at places like Inchinnan, Lochwinnoch, Arthurlie and Govan itself. The folk who commissioned these monuments, like the craftsmen who carved them, were the people known to the Anglo-Saxons as Cumbras and wealas. To modern historians they are ‘Cumbrians’, ‘Strathclyde Welsh’ or ‘North Britons’. At some point around the middle of the 11th century their homeland was conquered by the Scottish kings of Alba and the native royal dynasty was expelled. By c.1150, the inhabitants of Clydesdale had given up their ancestral language in favour of Gaelic. They were no longer Cumbri but had become ‘Scots’ like their new political masters. Inevitably, as time wore on, the deeds of their forefathers began to fade from memory. Soon only the sculptured stones remained, a handful of monuments scattered across the land, to bear mute witness to a forgotten people.